TCU DEI initiative plays role in encouraging younger, more diverse face of academia

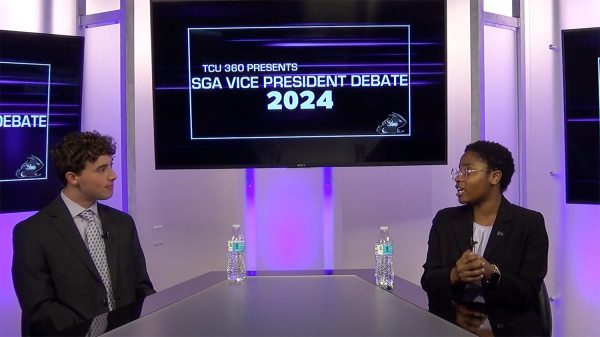

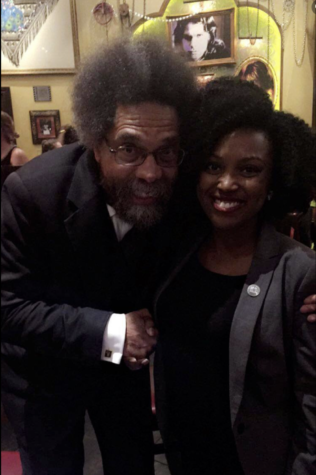

Dr. Jasmine Jackson, assistant professor of political science, participates in an undergraduate research opportunity at Duke University. (photo credit Dr. Jasmine Jackson)

Published Mar 6, 2023

Diversity lacking in higher education, studies show

Almost three-quarters of full-time college faculty members are white and, of the remaining quarter, only 4% were Black women, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, which reflect the fall of 2020.

As universities across the country seek to reframe hiring practices and promote diversity in academia, many have implemented diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) plans.

TCU’s own version of this plan started in the fall of 2016 with the establishment of the university’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion committee. The following year, the committee proposed a series of recommendations to increase institutional diversity. Among the approved proposals were an increase in efforts to retain underrepresented students, faculty and staff and implementing DEI as an “essential competency” in the university curriculum.

Since the inception of the DEI program, the number of BIPOC full-time faculty across all departments at the university has increased from 93 to 161.

Modern academic voice finds space at TCU

Those seeking the tangible impact of TCU’s efforts should look no further than the AddRan College of Liberal Arts. There, Jasmine Jackson, who holds a doctorate in political science, is an assistant professor of political science. Recruited through the DEI program, Jackson is currently the only Black professor in the department and is on track to earn tenure in 2027.

Originally, Jackson didn’t consider becoming a political scientist. As a teenager, she intended to become a biomedical engineer, taking calculus and physics classes to prepare. When she arrived in college, however, her aspirations shifted.

She met a political scientist doing research on the public evaluation of Black candidates based on hair texture and skin color.

“He’s telling us that he doesn’t understand how he’s getting these results that he recently got,” Jackson said. “And he’s like, I would just expect for people to think that the Black males with dreadlocks will be very enlightened. And he said, but that’s not what I’m getting.”

The researcher offered Jackson a place on his team after she proposed that public perception of Black candidates may be affected by cultural figures like rappers Lil Wayne and 2 Chainz.

“He sent me all over the country for the next couple years,” Jackson said. “I did an internship at University of California, Irvine. I did a research opportunity at Duke University. It really just made me realize, okay, grad school is it. I’m going to get my PhD in Political Science.”

Public political knowledge, measured in-depth

During an undergraduate research opportunity, Jackson opted to study whether Black people had less political knowledge than white people. One way of measuring political awareness is through a set of questions developed in 1996 by white political scientists Michael Delli Carpini and Scott Keeter. Questions included party control of the House, the percent of votes required to override a veto, the ideological location of major political parties and the ability to identify the vice president.

Jackson believed the questions were inaccurate in terms of measuring real political knowledge.

“While there is theoretical standing to these questions, at the same point, we have to recognize that as academics, we are in the ivory tower. And unless you get input from the public, you may ask the public things that are not relevant to their everyday life,” Jackson said. “Knowing who the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court is does not help you navigate state and local aid to feed your children. It doesn’t teach you how you fill out an unemployment form if you lose your job.”

Jackson chose the topic for her dissertation. She sought to develop a new set of questions, one that would accurately capture what the Black community knows about politics.

“What is really special about African-American political knowledge is that our knowledge is rooted in survival because of our distinct sociopolitical history in the [United States]. So I started trying to figure out ways that I could engage with the African American community to create questions that would adequately capture the knowledge that they had,” Jackson said.

Now in her first year of teaching, Jackson says she hopes her students learn to discuss politics and social issues with open minds.

“Learning how to talk about politics, to not be afraid to not know something, to engage in conversations about politics in a way where they do not feel attacked, and that they are open-minded enough to take what they need from that conversation, add it to what they already have, and let go of what’s not useful to them,” Jackson said.