Finding inner peace can be pricey. A pair of Lululemon Athletica’s signature yoga pants may set “Luluheads” back $100. A Manduka yoga mat, with a loyal following and reputation for its lifetime guarantee, durability, and slip resistance surface, can cost yogis $124 for the limited edition version. Drop-in yoga classes at yoga studios in Fort Worth are leveling out at about $20 per session, which can quickly start to add stress on the wallet.

You can even combine yoga with a getaway, but it won’t be cheap. Between April 24th and April 30th, there’s a six-night retreat at the luxurious Parrot Cay island resort in the Turks and Caicos with five days of yoga instruction. The cost? An easy $5,746.

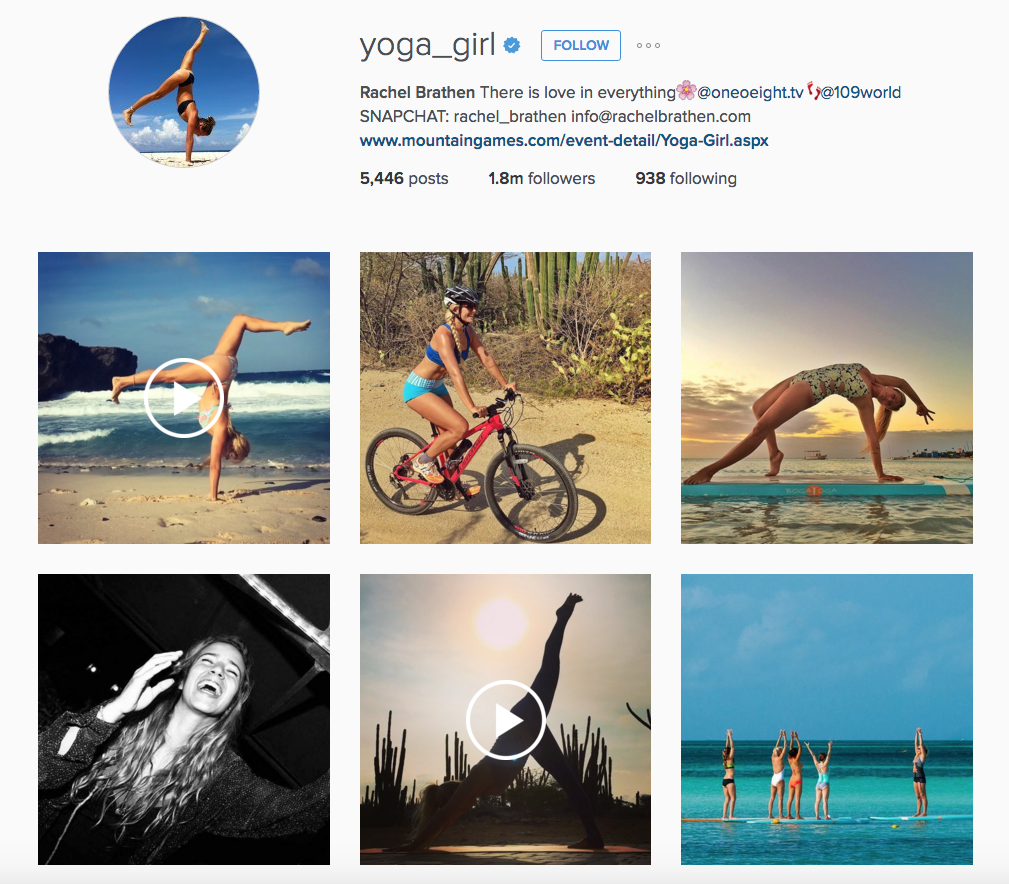

And in this age of celebrity, Pinterest, and Instagram, it is safe to say that yoga has something of a star status, with yoga teachers almost as recognizable as the Kardashians: The do-rag bandana doting Baron Baptiste. The Instagram-famous yoga girl Rachel Brathen. The cool-headed duo Sharon Gannon and David Life who taught Madonna and Sting.

And in this age of celebrity, Pinterest, and Instagram, it is safe to say that yoga has something of a star status, with yoga teachers almost as recognizable as the Kardashians: The do-rag bandana doting Baron Baptiste. The Instagram-famous yoga girl Rachel Brathen. The cool-headed duo Sharon Gannon and David Life who taught Madonna and Sting.

Yoga is a booming business.

A 2012 survey, collected by Sports Marketing Surveys USA on behalf of Yoga Journal, showed that the number of people practicing yoga increased 29 percent from 15.8 million in 2008 to 20.4 million just four years later. The survey also concluded that the actual spending on yoga classes and products, including equipment, clothing, vacations, and media nearly doubled from $5.7 billion to $10.3 billion in the same time period.

Now, some yogis are saying “peace-out” to all of that. There’s a growing resistance to the price, the pretentiousness, and the membership fees of mainstream yoga. Karmany Yoga, which opened its studio in 2011 on Hulen St., is at the forefront of the movement in Fort Worth, and is the only yoga studio with a donation-only, pay-what-you-can fee structure in the city.

The philosophy is on the front page of its Web site: “Simplicity and accessibility reign supreme … we’ve stripped away the pretentious setting, pricey membership fees, and restrictive class offerings that often end up excluding those who could benefit most from practicing yoga.”

It’s all about getting back to the basics, where members don’t have to worry about having the “right” outfit, “right” answers, or “right” payment.

“So many people don’t practice yoga or don’t continue to practice because they can’t afford it,” said Elyse Calhoun, the manager of Karmany Yoga Fort Worth. “There’s a lot of people who are really struggling and those are the ones that need it the most, so we offer yoga for whatever situation or place people are coming from.”

A new approach to a traditional teaching

On a Thursday night, soft candlelight fills the clean and simple studio on Hulen Street as instructor Elyse Calhoun stands at the door letting people in. An empty cardboard box sits on a small table in the corner of the room. Some students drop a donation in the box, some use small tablets to make a credit card donation, and some don’t donate at all. It’s 100 percent anonymous.

Mats, yoga blocks, and blankets are set out a few inches apart. People are socializing, chatting about their dinner plans, work days, and upcoming events around town. Quiet music plays in the background. There’s no opening “OMs” or chants. Calhoun instead starts with slow movements and deep breathing and then picks up the pace for a steady vinyasa flow. Yogis stay on their own mats, flowing and moving, as Calhoun helps members contort into difficult positions and encourages them to make cathartic HAA-sss as they exhale.

A priceless experience with value

Although it’s the only donation-based yoga studio in Fort Worth, Karmany isn’t the pioneer of priceless yoga. This “new wave” has been around for years and is popular in large cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Greg Gumucio, former student under the world renown Bikram Choudhury, revolutionized the concept of donation-based yoga in New York in 2010. At his studio, Yoga to the People, there’s no glorified teachers or star yogis. You can’t even reserve a time with a specific teacher. The only thing advertised about classes is the time and date. His manifesto is simple: “There will be no correct clothes. There will be no proper payment. There will be no right answers, no glorified teachers, no ego, no script, no pedestals … This is yoga for everyone … This power is for everyone.”

Gumucio’s business model relies on volume. Classes are mat room only and packed with a steady flow of vinyasas. According to the website, when a class is full, students are sent to another studio location and when that fills, they are sent to another. The idea, according to the website, is for the yoga to provide a service for people, not for profit. But the profit seems to follow the service. With three of his studios located in New York, two in California, one in Arizona, and others rising up across the country, it’s easy to see that the idea works.

From yoga in the park to simple, often crowded, and unadorned studios, donation-based or free yoga proves that yoga isn’t about a pristine environment. Yogis can practice in any setting and sometimes holding a pose with a foot in your face can really bring people together.

Although classes are far from empty at Karmany, with around 20 to 25 students in attendance, students say the community is something far different from that of a traditional studio. Because of the pay-what-you-can policy there’s a wider range of people. The stripped-down setting and price make yoga accessible to everyone, from old to young, novice to practiced, rich to poor.

“You don’t have to be any kind of certain way,” said Maria Svigos, a student at Karmany. “It’s a really supportive community full of different kinds of people and positive energy. The fact that the studio is donation-based opens it up for a lot of different people and definitely brings down the level of hesitation to try new things.”

Memberships at other local studios like The Yoga Project and Urban Yoga cost over $100 a month, while Karmany costs you only what you can afford.

Being affordable for everyone and accessible to anyone is great, but it’s a balancing act.

Teachers have to fulfill tandem goals of offering great, accessible and affordable yoga and paying bills. Those donations people place or don’t place in the box before class are the funds that keep both the studio and teacher afloat.

“The donations are how we get paid,” Calhoun said. “When people don’t donate, we don’t make any money, so it can be hard. But we’d rather people come every day and pay $2 than only come once a week and spend $15.”

Who’s to say what yoga is

Fort Worth rivals in the yoga world aren’t taking offense to the back-to-basics movement, either.

“I don’t really even have an opinion on [donation-based yoga],” said Jan Patterson, the Director of Operations at The Yoga Project in Fort Worth. “This is the only place I’ve practiced or taught, so I don’t have anything negative or positive to say about it.”

The donation-based model has its critics, though. When people can pay whatever they want, class size can increase. Detractors say when classes are too big, there’s not enough focus on breaking down advanced alignments and poses or on correct breathing technique.

But Calhoun said she is confident in the opportunities for growth and community that the donation-based system brings. Calhoun works with people individually during class to foster a welcoming community with room for growth and says that the pay-as-you-go policy only encourages people to keep attending and improving.

She shrugs off the skeptics with a slight smile as if to ask: who’s to really say what yoga is or should be?