US News editor defends rankings ![]()

See the full rankings ![]()

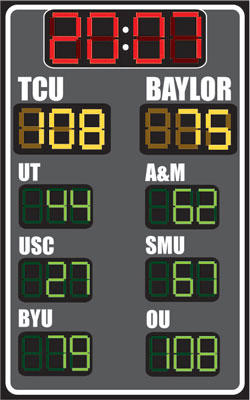

It’s the toughest time of the year for Lloyd Thacker to stand in a supermarket line. Thacker will be spending a lot of time looking at the publication he has dedicated himself to resisting.U.S. News & World Report’s annual college rankings hit news racks Monday – TCU came in at No. 108 along with the University of New Hampshire, Drexel University and the University of Oklahoma. Last year the university came in at No. 96.

Thacker, who directs the Oregon-based Education Conservancy, has led the growing nationwide opposition to the 24-year-old U.S. News rankings, which he sees as the epitome of commercialized higher education. Colleges should not be ranked based on a uniform scale, he said.

“It has distorted and skewed how (college) admissions are perceived,” said Thacker, a former college counselor. “Their impact far exceeds their educational relevance.”

A Disputed List

Ray Brown, dean of admissions, said most students who pay attention to the rankings are only looking for the most selective schools.

“Students who pay most attention to these rankings seek the Ivy League schools, like Stanford or Rice,” Brown said.

Alumni are more plugged into the rankings than students, he said, because they want to know how their alma mater is doing. And while some students may use rankings, there are many other tools potential students can use to evaluate schools, Chancellor Victor Boschini said.

U.S. News editor Brian Kelly defended the rankings. He said with thousands of colleges and universities available to students, the magazine is merely providing people a research tool. But critics say the influential lists lead schools to spend too much money in specific areas to boost their rankings.

“I think we get blamed for a lot of colleges’ behavior that isn’t our fault,” Kelly told reporters. “The kind of behavior they’re talking about here is often behavior that is good for the schools.”

The rankings reward colleges for small class sizes, student retention, graduation rates and financial resources. A quarter of each school’s overall score is based on the opinions of administrators at other colleges.

Surveying the Schools

In the last couple of weeks, Thacker has gathered signatures from more than 60 college presidents who have vowed to stop completing a major portion of the magazine’s annual survey, which analyzes 1,400 schools across the United States. The disputed section, which accounts for a quarter of a school’s score, rates a college’s reputation among its peers.

Among the institutions refusing to rate their competitors’ reputations are St. Mary’s College in Moraga, Calif., and San Francisco State University.

Boschini said TCU turned in the required data and cooperated with the survey.

In their hunger for higher rankings, some colleges have increased the number of scholarships for top-performing students, Thacker said. That system skews colleges toward more affluent students, while hurting low-income students who tend to have lower test scores.

Boschini said scholarships have nothing to do with TCU’s rankings.

Although other college administrators have long grumbled at the popularity and effects of the U.S. News rankings, school leaders have organized in opposition more than in years past. Thacker’s group is planning a September meeting at Yale University to discuss alternate ranking systems. Boschini said TCU wasn’t invited to the September gathering.

The Reliability of Rankings

This year, the magazine tweaked its rankings to compensate for the effects of low-income students, whose graduation rates are lower. Despite the change, some administrators say the rankings just don’t tell students enough about a college.

“The kind of work that U.S. News & World Report does doesn’t really get to the heart of what we do here at St. Mary’s,” said Michael Beseda, the college’s vice provost for enrollment. “They’ve narrowed the discussion in this country of what an undergraduate education should be.

“Any informed educator who thoughtfully thinks about the ranking systems realizes they are inadequate.”

But at the University of California at Berkeley, the top-ranked public university in the country this year, administrators say the lists offer valuable information when taken in the context of other sources. Any rankings systems will have their supporters and critics, said Christine Maslach, the university’s vice provost for undergraduate education.

“You always have to take these with a grain of salt,” she said. “There’s probably a variety of places where a student would do well.”

Not Much Sway

Despite the growing opposition, U.S. News remains a major player in the world of college choice. At least 97 percent of the schools that participated in this year’s U.S. News rankings plan to continue to do so, according to a survey of more than 300 admissions officers released last week by Kaplan Test Prep and Admissions.

And while some say the rankings continue to sway many graduating high-school seniors – especially those at the most competitive high schools — TCU’s Brown disagrees.

“In my experience – and I’ve- been doing this for a long time – almost nobody bases their decision on these rankings,” Brown said.

Katherine Lewis, a freshman fashion merchandising major, said she and her parents looked at the rankings, but it wasn’t a large factor in her final decision.

“Rankings helped,” Lewis said. “But my final decision was based on seeing this campus.”

Matt Krupnick of the Contra Costa Times and staff reporter Antoinette Nevils contributed to this report