Former associate executive editor of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram Phil Record still remembers how Sam Baugh tried and failed to teach him how to punt when Record was 7 years old.

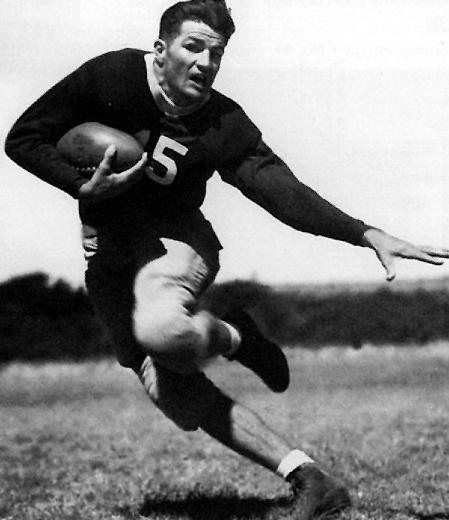

That’s about the only thing TCU football legend Baugh couldn’t do on a football field.

Baugh, who was 94, died Wednesday, but Record and others are remembering the two-time All-American for his life on and off the field.

Record said he lived across the street from the TCU team doctor, and on Sundays when Baugh and other players would have dinner with the doctor, some team members would join Record and the other neighborhood children who were playing football.

TCU alumnus, best-selling author and official historian for the National Football Foundation and College Hall of Fame Dan Jenkins called Baugh “the greatest player in TCU history and one of the greatest in the history of college football.”

Born in Temple, Baugh led TCU to a national championship in 1935 under coach Dutch Meyer, Jenkins said in an e-mail. Baugh led the nation in both passing and punting that year and the year following, Jenkins said.

In that bygone era, players had to play both offense and defense, which proved difficult because players were much heavier than they are today, Jenkins said. That still didn’t stop Baugh from throwing passes so hard they would often knock down the receiver, Jenkins said.

“Sam changed the way football was played and coached. He took Dutch Meyer’s spread and triple wing and made the passing game a major weapon,” Jenkins said. “In Sam’s day, the pass set up the run. He took that scheme to the Washington Redskins and won two NFL championships with it.”

Even off the field, Jenkins said Baugh retained his roughness.

“He was a rough-edged, tobacco-chewing country boy but likable and friendly and never met a four-letter word he didn’t like,” Jenkins said.

When Baugh was a freshman, he and several friends went to Baylor University to kidnap the team’s mascot bear, Jenkins said. Baugh and his friends were caught and had their heads shaved and painted green and gold, Jenkins said.

Jenkins, a Fort Worth native and TCU graduate from the class of 1953, said that to this day he doesn’t know how much of that story is myth. But he said when he approached Baugh about the story’s authenticity, Baugh’s reply was that it was “kind of true.”

Record, now a professor of media ethics at TCU, remembers the softer side to Baugh and calls him a “friendly country boy.”

“He used to try to teach us to pass the ball, and I always wanted to be a punter,” Record said. “There was just something there that didn’t work although I was getting lessons from the world’s greatest punter.”

Jenkins said that from the age 6, his family took him to every TCU home game and that he can remember how Baugh played better than what he did previous week.

Although there have been several reports about where and when Baugh received his “Slammin’ Sammy” moniker, Jenkins said the name came from a Star-Telegram writer and former TCU football player named Amos Melton, who coined the nickname in 1934. Jenkins said Baugh hated being called “Sammy” and that sportswriters who had never seen him in action called him by that name incorrectly.

Whether Baugh was around teaching children how to punt or joining football’s elite for one last time, he was always in good company.

Baugh was the last surviving member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s inaugural Class of 1963. Jenkins said other inductees from that year include Green Bay Packers coach Earl Lambeau and former Olympian Jim Thorpe.

“Pretty good company, if you know a thing or two about football history,” Jenkins said.