The U.S. government has spent trillions of dollars training and equipping servicemen and women to be instruments of war, but it spends only a fraction of that amount on transitional services to help them adjust to life at home.

The transition from combat to college student is a difficult one. Being a veteran in a college classroom is one of the loneliest positions people can find themselves in. A 25-year-old veteran may find it hard to relate to an 18-year-old freshman who is out of Frog Bucks, and dreading the conversation with his or her parents. This veteran may have had the experience of commanding a platoon, squad or fire team in combat situations where some people didn’t make it home.

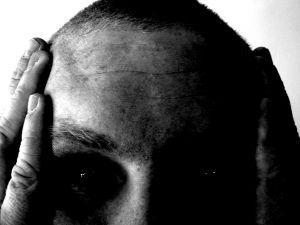

I spent 11 months and eight days as a Marine in Iraq between 2003 and 2005. The sights, sounds and smells of that experience still haunt me. The decisions that I had to make required split-second timing, and after the guns fell silent I was left with a lifetime to analyze those decisions. This analysis, in the form of nightmares and daydreams, can lead to a life of bitterness and regret.

Experts call this condition post-traumatic stress disorder. I call it reality.

The disorder manifests in a variety of ways. The effects most often take the form of nightmares, jumpiness, anxiety in large groups and depression. Many combat veterans have trouble dealing with this disorder, leading some to seek comfort in alcohol or drugs. Others lose this battle and take their own lives to escape the pain.

It is imperative that the government takes responsibility for the silent killer of America’s veterans and develop long-term programs to help adjusting veterans.

When I came home and started college the culture shock was more extreme than my transition experience from civilian to Marine. While I was in the Marines my patience shortened and my temper sharpened. When I got out anger dominated my emotions and alienated me from my new peer group. I found comfort in loved ones and friends who, through our conversations, had in some way shared my experience.

The hardest thing for me now is seeing a flag-draped coffin or a news report about more Americans dying in Iraq or Afghanistan. When I see those things I am instantly transported back to the dust and blood of Iraq. War is a terrible business from which veterans can never truly return. I pray that my healing process will begin when the last American comes home from this war and the help they need is available to them when they get there.

The military training we receive is adequate to keep us alive in combat, but the training we receive to help us adjust to life outside of a combat zone is subpar at best. More post-service counseling should be given to veterans suffering from PTSD to ensure their continued recovery from the psychological effects of war.