Iranian-American academic Haleh Esfandiari went on a routine trip to Iran in 2006 to visit her mother. On her way to the airport on Dec. 30 that year, she was robbed and lost both of her passports. Little did she know that when requesting new travel documents she would be barred from leaving Iran and imprisoned for months.

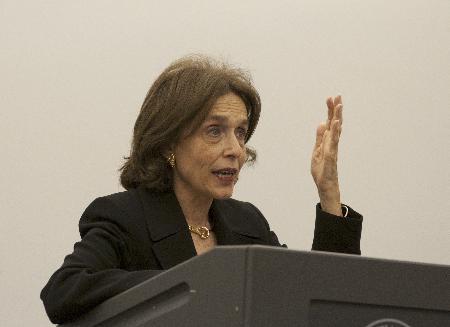

Esfandiari, director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., spoke in the Steve and Betsy Palko Building about her new book, “My Home, My Prison,” an account of her arrest on false charges and lengthy incarceration at the Evin Prison in Iran.

Esfandiari was taken and interrogated by the Iran Intelligence Ministry about her involvement with the Wilson Center.

“I very quickly concluded Iran was truly paranoid regarding the U.S. visiting Iran,” Esfandiari said. “They convinced themselves the United States tried to overthrow the regime.”

Their interrogations lasted eight to nine hours a day for four months, she said.

“They convinced themselves they arrested a ‘big fish,'” she said.

The interrogators spoke little English and were completely brainwashed, she said.

“They’re there to break you and make you talk and tell him exactly what he wants to hear,” she said. “So he could go and report, ‘Yes, she said this or that.’ And this or that meant, ‘Yes, the United States is planning to overthrow the regime’ and ‘Yes, the (American) centers invited the Iranian scholars and tried to introduce them to agents of the United States.'”

The Iran Intelligence Ministry has an obsession with figuring out the United States, the former Iranian prisoner told her audience.

On May 8, the interrogators gave Esfandiari an arrest warrant, and she was taken to the Evin Prison, which is infamous for making people disappear, she said.

“I froze and I panicked,” she said. “I knew this was going to be my home for I didn’t know how long.”

In prison Esfandiari was falsely accused of adultery, being married to a Jew, being a spy for the CIA and having lived in Israel, she said.

The low point of Esfandiari’s stay in prison was being asked to appear on camera to talk about the Wilson Center, she said.

“(I knew) quite well that they will slice it and cut it and then sort of paste it together,” she said.

The president of the Wilson Center wrote to the Iranian government and asked for Esfandiari’s release, she said.

“For the first time in 27 years the supreme leader had reclined to a high American official,” she said.

After Esfandiari was released, she was told she was not allowed to leave the country, she said. Ten days later she was told she could return to the United States.

“As the stewardess closed the door to the plane, this time the banging of the door meant that I was free and I can go home and return to the United States,” she said.

Esfandiari said she believes the Iranian interrogators did not physically harm her because of the uproar following the murder of an American journalist two years earlier.

“Maybe they thought, ‘When you go out, you can tell that Iran is not such a horrible place,'” she said.