Some college students don’t want to return to their hometowns because they’re “lame,” too sleepy or too small8212;rarely is it because of danger, violence or fear. But for senior studio art major Frieda Verlage, the cartel violence in her hometown of Gonzalez, Tamaulipas Mexico, is a real, life-threatening worry.

Tamaulipas is a border, state along the southern-most tip of Texas in the Gulf of Mexico where minimum-wage workers earn around $4.50 per day in foreign-owned factories. The state is also ground zero for a war between two of Mexico’s most powerful criminal organizations, the Cartel del Golfo and their former allies, Los Zetas.

The violence first erupted in 2006, when Mexican President Felipe Calderon took office. Prior to that, the Cartel del Golfo was the dominant trafficking organization in Mexico. According to the Stratfor congressional research report, the cartel’s reputation for ruthlessness was a creation of the cartel’s enforcement arm, Los Zetas, which was founded by ex-commandos and Mexican police.

When Calderon came into office and declared war on narcotrafficantes, many of the arrests were targeted at the Cartel del Golfo, allowing Los Zetas to gain dominance and territory. But the power struggle, which is mirrored in other cartels in other parts of Mexico, has left more than 28,000 dead since Calderon’s election.

Comfortable and secure at her university home, Verlage is safe from the violence that rages on across the border, but she worries about her family every day.

“There are signs posted that say not to go out after 9 p.m.,” she said. “My mom can’t even drive for the most part.”

Verlage said that because her mother drives a new black Ford Expedition, exactly the type of vehicle preferred by the cartels, she is afraid something will happen to her or they will take her car.

“My mom and her friends used to have lunch at each other’s houses and have get-togethers and just talk, but they can’t even do that anymore,” she said. “No one leaves their house unless they have to, it’s just too dangerous.”

Balancing the books for her grandfather’s company, Verlage’s uncle was surprised to find that his father had not been paying the “cuota,” or regular extortion fee the cartel charges to businesses for “protection.” She said her uncle warned her father that something could happen to them, but her grandfather declined on principle.

“He told my uncle he wasn’t going to give in to their threats. He’s very prideful, and he refused to give in to their demands,” she said. “He didn’t want his money to fund them.”

Not soon after Verlage’s uncle warned his father, Verlage said her uncle was abducted and held by the cartel for a week. Although he was returned to the family and was not physically harmed, Verlage said he was emotionally distraught and may have witnessed an execution.

Verlage’s grandfather began paying the fee.

Verlage said a lot of people have turned to the Internet to get the real stories behind the violence.

“When the violence started, people started using blogs because the news wasn’t reporting anything and people were scared,” she said.

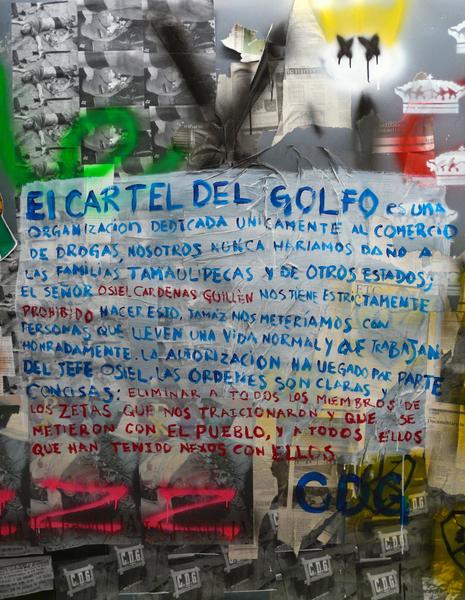

It was on a blog purportedly maintained by the Cartel del Golfo that she found the words that inspired her largest piece. In the center of the wall-spanning artwork is a message to the people of Tamaulipas.

In English it reads:

“The organization is dedicated only to the commerce of drugs. We would never harm the families of Tamaulipas and other states. The boss says it is strictly prohibited to do this. We would never harm people that have a normal life and an honest job. The authorization has arrived from the boss and the orders are clear and concise: to eliminate all members of Los Zetas who betrayed us and involved the people8212;and all those associated with them.”

And, though wary of the violence, Verlage said she is intrigued by the complexities of life with the cartels. On one hand, she said, there is death and violence and terror, but on the other a strange relationship with the people of the town, who are for the most part resigned and cooperative.

Gonzales is a rural community where the ranch-style houses have lots of acreage between neighbors. Many of the cartel soldiers, Verlage said, were born and raised in the town and there is some comfort in knowing they are “hometown boys” and the lesser of two evils. But these “hometown boys” are trafficking marijuana, cocaine and more often these days, methamphetamines.

“It’s hard because you know they’re not the good guys, but they’re considerate enough to tell you to be careful,” she said. “You have mixed feelings because you know they’re bad people, and all the death and shootings in the middle of the night and everywhere, but then you’re like, “aw, but they’re telling you to be careful,’ so you don’t really hate them that much.”

After her graduation in May, Verlage said she does not intend to move back to Tamaulipas. She will start a new life someplace bigger, more cultured and art-centered. As for her cartel-inspired art, she said that much to her dismay, she will probably have plenty of inspiration to expand on her series. She said the people of Gonzalez have been told that the violence would come to an end sometime this fall, but she doubts it.