Higher education has been the battlefield of a war on free speech and TCU is taking this crisis head on.

Acadia University’s Dr. Jeffrey A. Sachs came to campus to refute the idea that there is a free speech crisis on college campuses. Keith Whittington, a professor at Princeton, said differently last year.

“Some spoilers: there is not a free speech crisis,” Sachs said. “Last year, there was widespread belief that there was a free speech crisis. This is the first time ever restrictive speech codes dropped below 50% for private universities.”

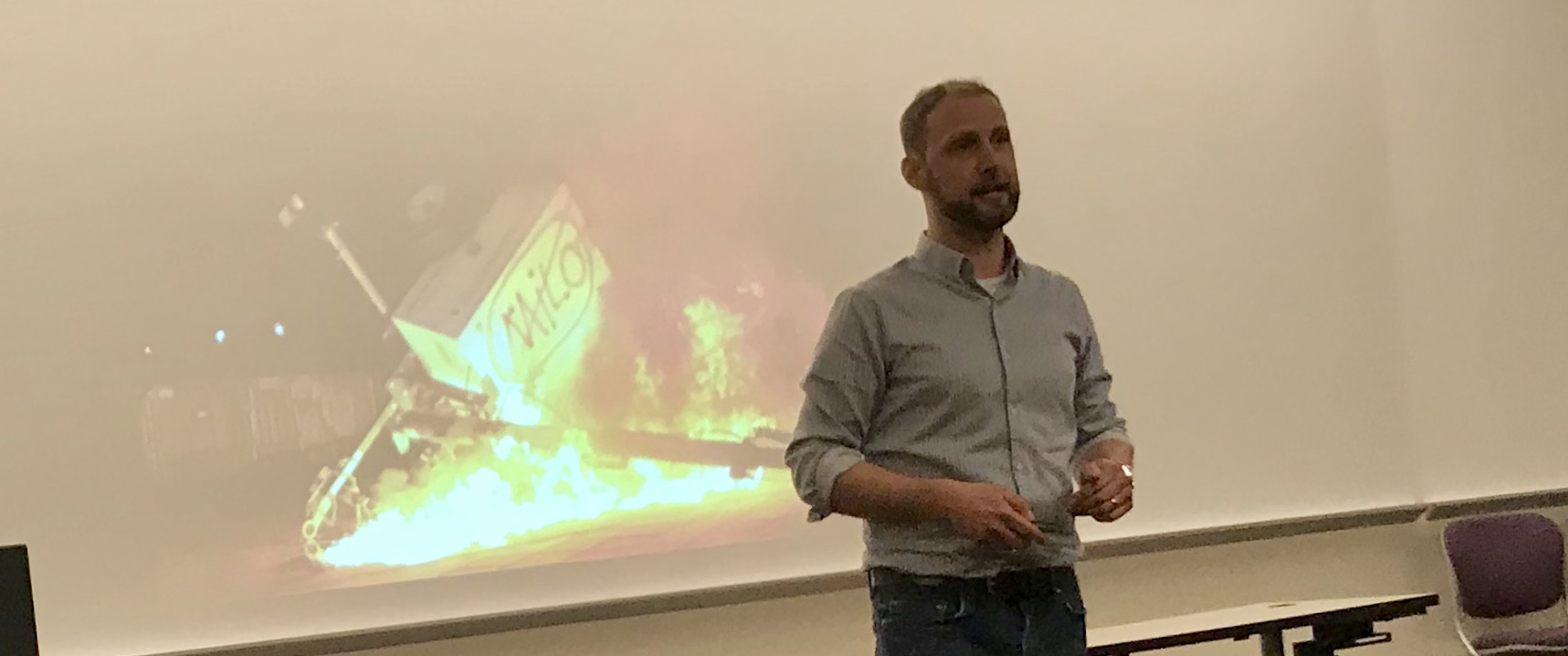

There was a spike in conflict over free speech in 2017, but it plummeted the following year. Now, Sachs credits a change in institutions and student behavior.

“The university has been well and sucked into the American culture, and it has to be pulled out,” said Sachs. “If not, then it will pull the university apart.”

Acts of speech began boiling into violent

“It’s no mistake it kicked off in 2016 and 2017,” Sachs said. “Whether you love or hate Trump, admit the 2016 presidential election changed America’s atmosphere. What went right in 2018, what is changing?”

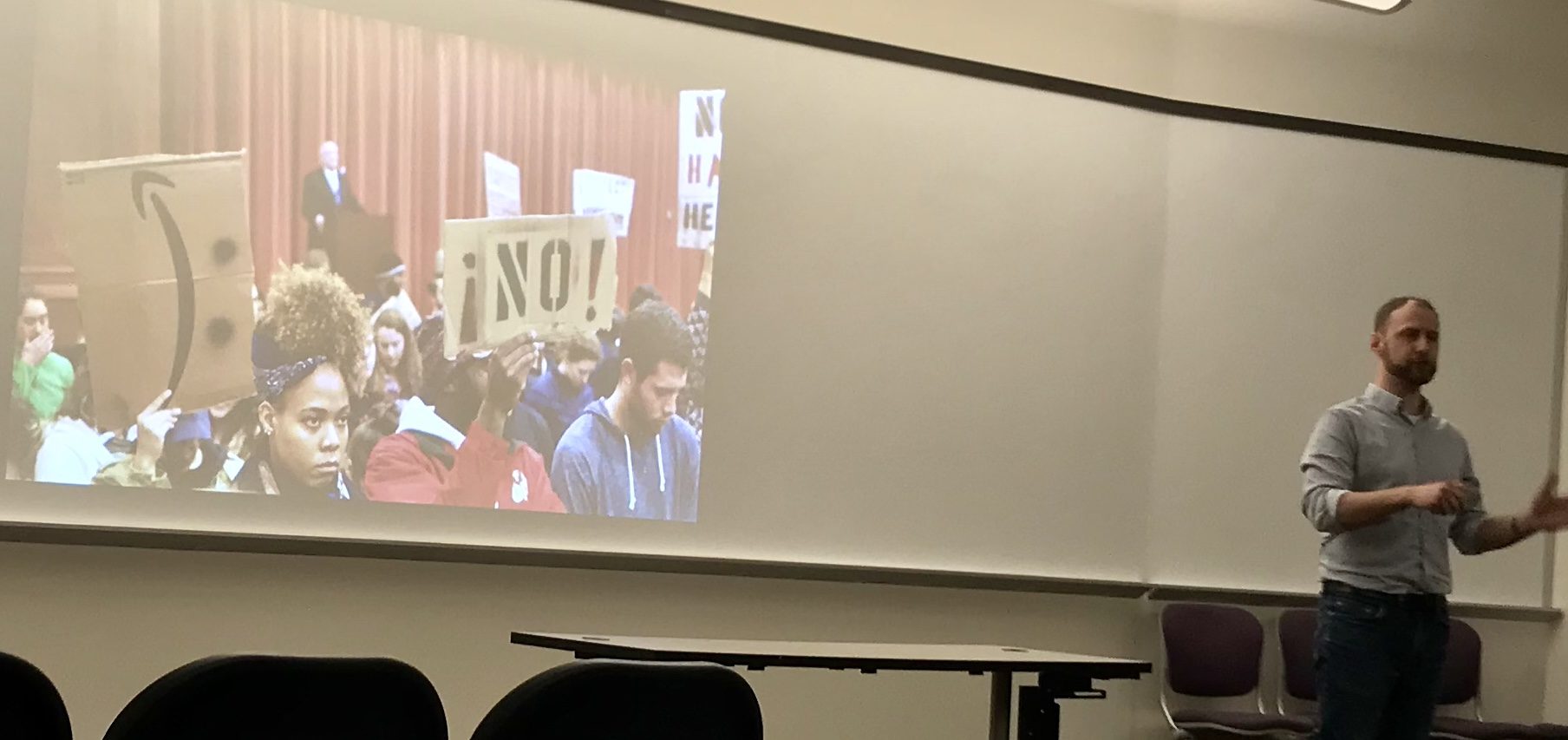

College campuses aren’t where these problems originate; rather, it’s the platform where political agendas battle it out.

“These are immediate manifestations that students were already concerned about,” Sachs said. “I’m not just pulling this out of thin air, I talked to actual activists themselves, and this is what they said.”

Sachs said while the debate regarding free speech may not be considered a crisis, there are still problems that need to be taken seriously.

“That being said, I feel solutions are more likely to come from on campus than off campus,” Sachs said. There has been a learning curve in institutions and student behavior.

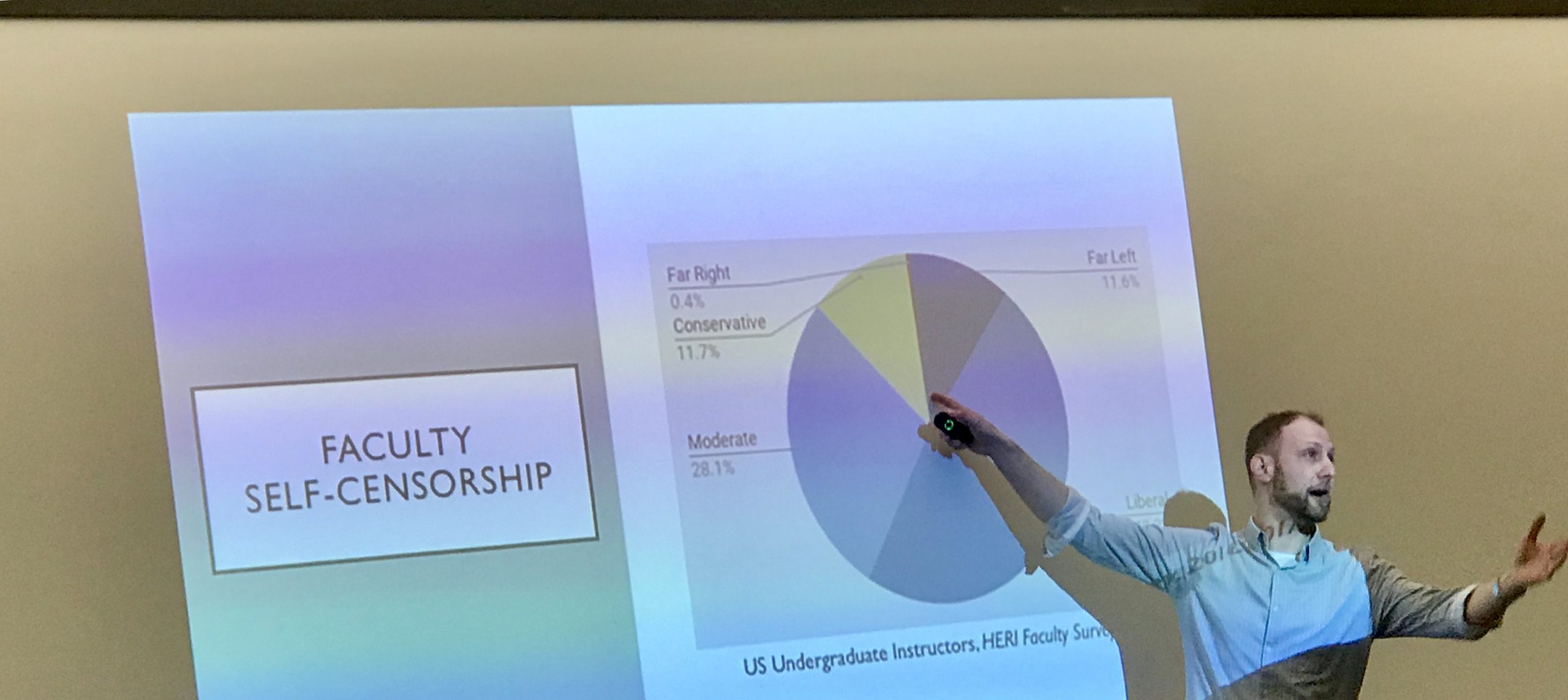

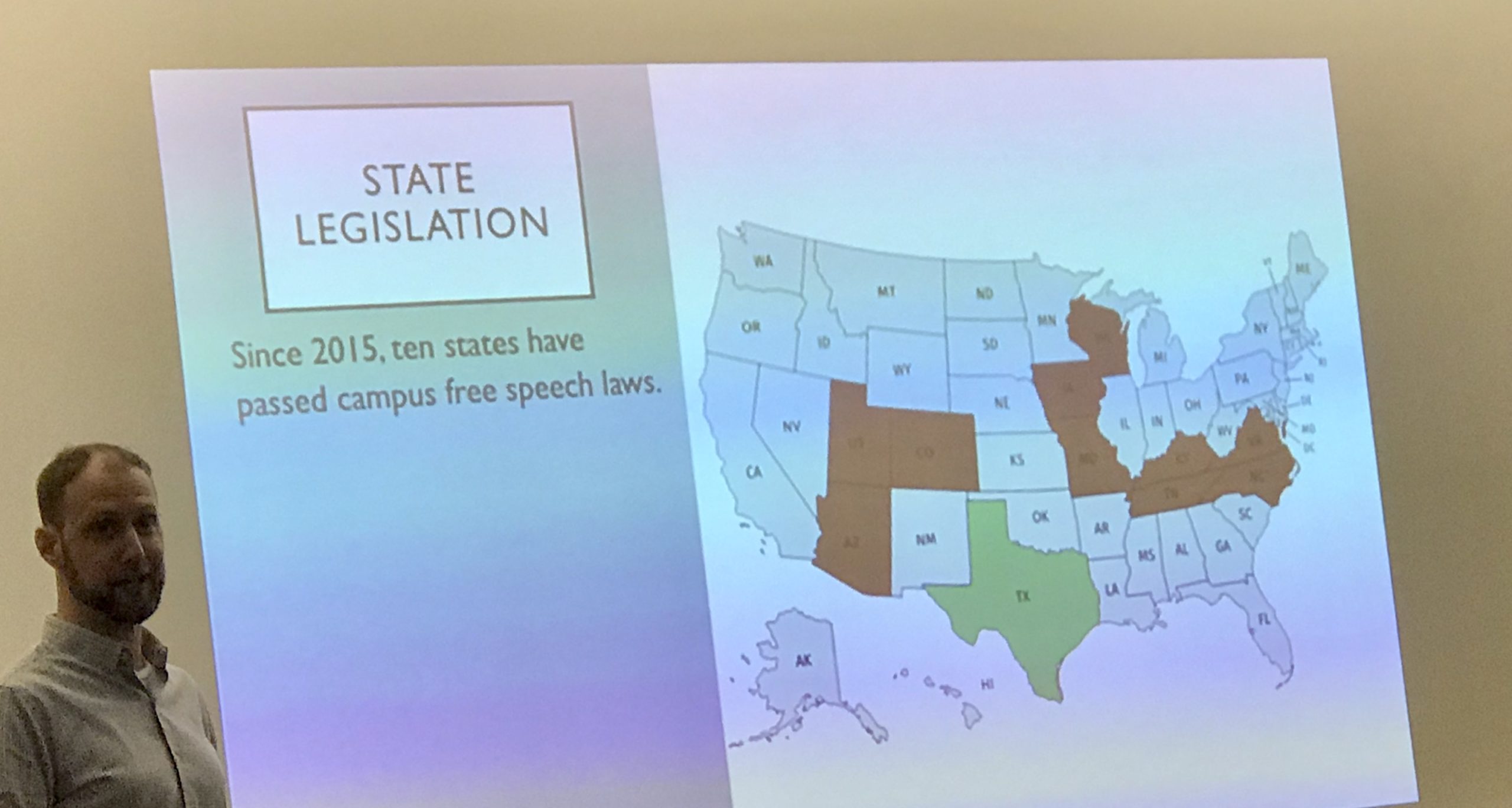

Political regulation of campus speech by state legislators and faculty and student self-censorship are serious threats to free speech.

“Censorship is notoriously difficult to discover, it’s the absence in something,” Sachs said. “How do you measure an absence?”

People most commonly censor themselves because they want to fit in, and it’s no different for the 11.7% of conservative faculty.

“I think this needs to be studied more,” Sachs said. “Regardless, it’s naive to think conservatives do not self-censor.” People on b

“I was most shocked that 40% of professors are liberals,” said Madelyn Gabbert, a TCU student.

“As a professor, I worry I don’t pay enough attention to my students,” Sachs said. “Believe it or not, professors really do want to know what you think, so take that with you and start talking in class.”

Student censorship is mainly a result of uncertainty and wanting to fit in. Sachs said that 90% of students feel comfortable enough to express themselves.

“If there is going to be a change, it’s going to come from everyday interactions with faculty and students,” Sachs said.

TCU professor Dr. Manochehr Dorraj asked how political correctness impacts self-censorship.

“I don’t think I know what political correctness is,” Sachs said. “One person’s civility is another person’s political correctness.”

He said it was impossible to come up with a universal definition, and he challenged the audience with the task.

“Everyone overwhelmingly feels comfortable expressing themselves,” Sachs said. “That’s great, but everything is not hunky dory, other threats do persist.”

Speech is threatened by state legislators passing laws on free speech, because it will likely backfire. Ironically, the laws to protect free speech may be the downfall.

A cultural security dilemma is suffocating trust, and the public’s cyclical hysteria and paranoia is fertilizing the political divide. One group’s offense is being perceived by opposing groups as defensive preparation and vice versa. Seeking security has resulted in insecurity.

“We might see less free speech as a result,” Sachs said.

Boycott, Divestment

“I’d heard about BDS before, but he really put it into context,” said Jack Fritschy, a TCU student.

Sachs said we face these threats by “keeping calm and carrying on.”