Overcoming obstacles: graduate faces challenges inside, outside classroom

Published May 3, 2019

PKG_SICKLE CELL from Carolina Olivares on Vimeo.

“Big money!”

That’s how the senior economics major is known across campus. He thrives on making people laugh and can’t seem to go anywhere without knowing someone. On the off-chance he doesn’t, he just makes a new friend.

Tafari Witter grew up in the south Dallas neighborhood of Pleasant Grove, a world away from TCU. But come May 11, he’ll cross the stage in the Schollmaier Arena.

His Horned Frog journey was unexpected.

“People in the neighborhood have the mentality that you can only get out by becoming a basketball player, a football player or a rapper,” said Tafari.

Dreams of college hoops and later the University of Texas at Ausdtin marked his plans until he was accepted into the Community Scholars Program at TCU.

By then, life had taught Tafari to be flexible. He’s lived every day with sickle cell anemia. The chronic blood disease that causes red blood cells to be “C” shaped, rather than flexible and round.

Sickle cell can shorten a person’s life expectancy by 20 to 30 years.

Centers for Disease Control

The “C” shaped cells can get hard and sticky, and when they die off, they can starve the body of oxygen. They can also get stuck or clog blood vessels. Either situation can trigger a health crisis that can be fatal.

Tafari had his first major crisis as a 7-year-old and his most recent as a first-year student — he doesn’t remember either.

Dreams of Basketball

His mother, Jennifer Levy, is still haunted with memories of that first crisis. Tafari’s eyes and skin were yellow, and his body burned with 101 degree fever. The pain was so excruciating it hurt to move.

“I saw a totally different person that day,” Levy said.

By the time she got him to the hospital, his blood levels were so low that the only way doctors could treat him was with a blood transfusion.

Once the crisis ended, Levy got her little boy back — a bundle of energy who busted out dance moves and always seemed to have a basketball in hand.

“I thought he was going to marry that ball.”

Jennifer Levy

Tafari wanted to be the next Derrick Rose, who at the time played point guard for the Chicago Bulls.

As a toddler, he sat on the bench watching his older brother’s practices, mesmerized at every drill they’d run.

“He was always coming in … his legs weren’t even touching the floor yet,” said Donnell Hayden, who coached both Tafari and his brother.

Hayden said Tafari, or “Tafa,” as his friends and family call him, wasn’t an average kid playing for fun.

He took the game very seriously and had a very high basketball IQ, so much so that Hayden moved him up to play with the older kids.

Tafa was special, Hayden said, adding that he had never had a player like him:

One who responded with “Yes sir” and “No sir.”

One who headed straight to practice from school, bragging about the spelling bee award he had just won.

One who played inside jokes on him, asking things like what the color blue was.

Hayden, smiles as he remembers his response: “Well, I know what the color black is — get on the line.”

“He was just so extraordinary in his mind that he didn’t even need basketball to survive,” said Hayden. “He was going to make it even without basketball, but I never told him that because he enjoyed it so much.”

But sickle cell complicated the game.

The exertion from running up and down the court puts Tafari at risk for dehydration, which can trigger a crisis.

Still, in high school, he was captain of Lincoln High’s basketball team. During game time, his mother could be heard yelling for him to get water, but Tafari was alway reluctant to leave the court.

The key to avoid sickle cell crises is to stay hydrated. However, his teammates on intramural don’t think there’s a bigger reason as to why Tafari takes a gallon jug of water with him to every game. (Carolina Olivares/Staff Reporter)

But playing in college wasn’t an option. Because of his health, he couldn’t even make TCU’s basketball team as a walk-on.

Pursuing Education

Growing up, Tafari’s parents stressed education. Grades, not scoring averages, were what interested his father.

Tafari said he’d come home from school with his report card. Sure, his father was proud he had an A in every class. But he would challenge Tafari to raise those As that were in the low 90’s.

Tafari graduated as the class valedictorian, but Lincoln didn’t offer the rigor that many TCU students faced in high school. About 91 percent of his class graduated on time, according to the Texas Academic Performance Report. Less than half of all students were deemed “college ready” in English language arts and math.

“I don’t hesitate to say that in our African American communities, education is not really top priority in our kids,” said John Carter, one of the coaches at Lincoln High. “To have someone as young as he was be an example for his peers was powerful.”

At TCU, Tafari pushed himself to meet the 3.0 GPA requirement for Neeley.

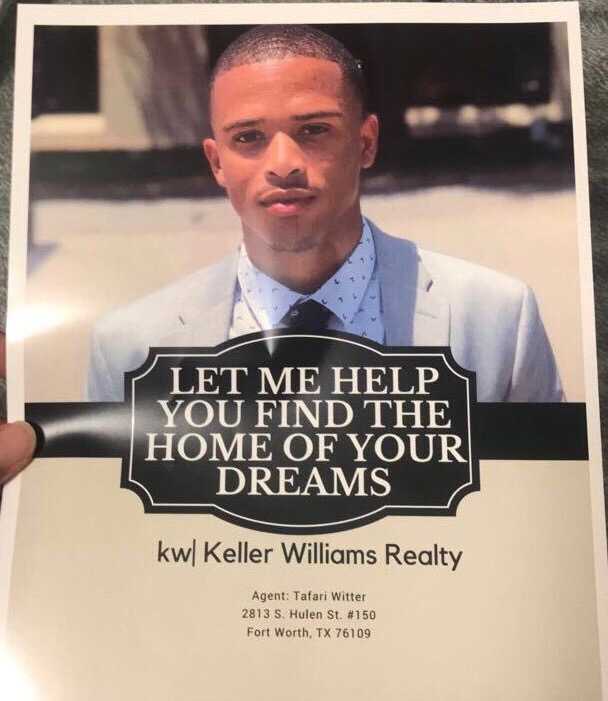

Tafari got his real estate license about a year ago. He works at Keller Williams. While many students were soaking in the sun on a beach or skiing at a resort over spring break, Tafari was doing home visits with a client.

He has yet to close deal, but he’s not deterred. He understands that many prospective clients think he’s too young and inexperienced to sell them a house.

“The reason I put such an importance on money is because I grew up not having it, and I want to be able to have so much money where I can get my mom out of that neighborhood,” Witter said.

The business-driven animal inside him came out when he was in middle school. He said he would sell just about everything from candy, erasers and shoes to make a little extra money.

Witter said his main goal in life is to be an entrepreneur. The idea came to him when he was 16 years old and starting his first job at Marshall’s, opening packages and hanging new merchandise.

For him it was just a summer job, but he realized that same job was what helped feed his co-worker and his family.

Tafari’s Why from TCU Student Media on Vimeo.

“The reason I want to be so successful is for that one kid, that one person that I can impact,” said Tafari. “Everything that I’m doing is bigger than me. I think I was born to make an impact on the world by leading by example.”