Second-Hand September, an initiative started by the UK charity Oxfam, is encouraging consumers to go 30 days without purchasing any new clothing by renting, trading or choosing second-hand.

Jana Pimentel, a TCU alumna who graduated last year, is working to raise awareness of the campaign and encourage others to participate.

“What they’re promoting is for the month of September, instead of buying new clothing, and I would actually say to extend that to just about anything, to shop second-hand instead,” said Pimentel. “So that’s really the main goal and just to bring awareness to the environmental impact of the clothing and textile industry.”

One of the fashion industry’s most damaging impacts comes from the fast fashion cycle.

Read more: TCU fashion students adjust to a fashion industry changed by COVID-19

Dr. Shweta Reddy, who teaches a course on sustainable fashion at TCU, said fast fashion is the rapid and wasteful production of clothing that harms workers and the environment.

“It’s a very short production to floor,” she said. “In 68 days, if you have to make the textile, cut the textile, sew it and put it onto the shelf, it’s basically putting pressure on a lot of people.”

Popular brands including H&M, Boohoo and Forever 21 manufacture clothes for as many as 52 “micro-seasons” each year, according to The Good Trade. The quick turnover keeps inventory flowing in, encouraging consumers to toss out items they bought weeks before to purchase outfits that are in style.

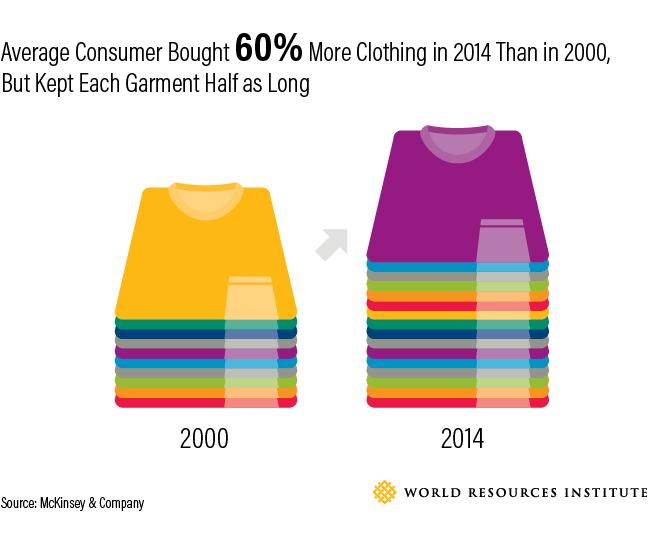

The average American bought more than twice as many clothes in 2014 as in 2000 but sends 70 pounds of clothing to the landfill each year, according to Council for Textile Recycling. Nearly all of the clothes could have been recycled or repurposed by manufacturers.

Fast fashion takes a toll on the planet. The industry is the second-largest water polluter in the world, according to the U.N., with the oil industry in first.

Clothes with synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon and spandex are made with oil-derived petroleum and release greenhouse gas emissions as they rot in landfills.

Many companies that sell clothes and other textile products in the U.S. put workers at risk when their manufacturing occurs in countries with limited labor and safety laws.

“Most workers in the fashion industry are underpaid, overworked and mistreated,” said Brooke Prock, the artisan production coordinator for Fort Worth sustainable clothing outlet Tribe Alive.

The outlet pays its artisans a living wage as part of its mission to make clothing sustainably, from producing synthetic-free items using minimal energy and water to eliminating single-use plastic.

Workers may also be exposed to toxic chemicals. Of the 2,000 different chemicals used in textile processing, just 16 are approved by the EPA, according to sustainable fashion brand Reformation.

Next steps for consumers

Second-Hand September is just one of the solutions to increasing environmental and social sustainability in fashion.

The number of sustainable outlets like Tribe Alive is growing, but Prock said the concept of sustainable fashion still needs wider acceptance.

“We need to create an environment where it’s expected and normal to pay a fair price for a top you will wear a long time instead of being able to pay $7.99 for a top you will wear three times.”

Brooke Prock, artisan production coordinator at Tribe Alive

Pimentel said students can help the sustainable fashion movement with small actions, such as purchasing gently used accessories or buying classic clothing from eco-friendly companies that won’t go out of style.

Reddy also stressed the significance of the consumer on making the industry more sustainable.

“You’re basically voting when you’re buying a garment,” she said. “You make a choice every day, every time, actually, that you’re buying a piece of fabric.”

Most sustainable fashion companies have a page on their website discussing their environmental and human rights practices.

Prock says being a sustainable fashion consumer not only means purchasing sustainably made clothing, but also keeping items longer and donating or trading unwanted items.

“I think everyone should evaluate their own closet,” said Prock. “If consumers were educated on the true cost of producing quality pieces with fair labor, I believe the fashion industry would naturally move towards a healthier, more sustainable place.”