After four years of silence, Yik Yak, a social media app that critics claimed facilitated racism, discrimination and threats of violence, is back.

The app that lets people within a 5-mile radius anonymously create and view discussion threads is once again active on TCU’s campus.

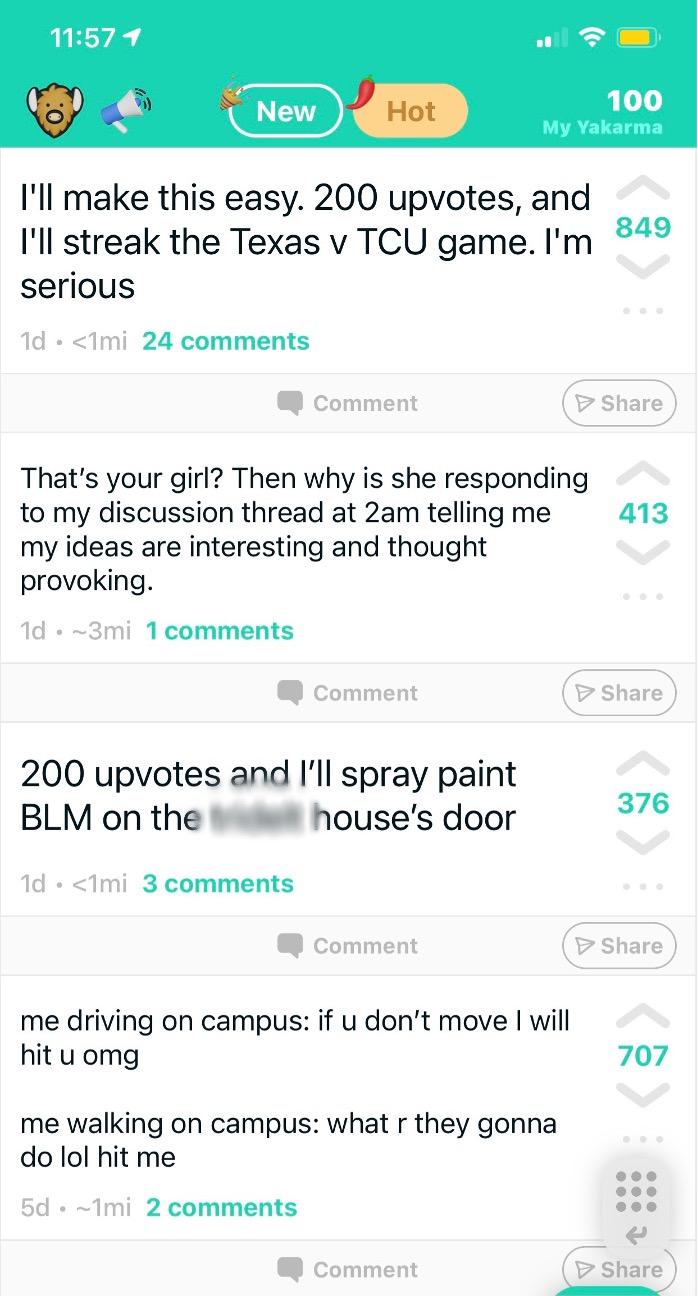

Yik Yak’s design is simple: people create posts, called “yaks,” that can either be upvoted, downvoted or commented on by other users. Users receive reputation points, called “yakarma,” when their posts are commented on or upvoted multiple times. The points are also kept anonymous to other users. Users can pay an additional fee to reach a wider span of users beyond the 5-mile radius.

At TCU, some posts discuss upcoming events on and off campus. Others capture users’ opinions on topics regarding life on TCU campus, such as favorite places to dine on campus or offer advice to other students.

The app was launched in November of 2013. Co-founders Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington, graduates of Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, designed Yik Yak to connect and provide a voice to college students on campuses. But the app quickly faced scrutiny by college administrators and others who said it allowed users to attack others anonymously.

This isn’t the first time that Yik Yak has made an appearance on TCU’s campus. Yik Yak originally hit campus in early March 2014, spreading quickly among students. Students created and posted hundreds of posts each day, but the app was scorned after some users began making racists comments during the Baltimore riots of 2015. Two years later, after a drop in users, the app was shuttered.

Several students at schools and universities across the United States petitioned for geo-fences or the app to be banned, according to the New York Times. In August of 2016, the company decided to backpedal on its claim to fame and force users to use usernames for their posts, according to Newsweek. By 2017, Yik Yak was shut down.

The company used to be worth $400 million at one time, according to Forbes, but its stock quickly dropped because of death threats, bomb threats, school shooter threats, bullying, harassment, racism and more.

According to the app’s website, its new owners, digital payment processor Square Inc., purchased Yik Yak for $1 million in February with a promise to take a stronger stand against cyberbullying and abuse.

Yik Yak added a “Mental Health Resources“ page, along with a “Community Guardrails” section on their site. The site also said there are now policies regarding “bullying and hate speech,” but in the past weeks, there have been conversations that single out Greek organizations or talk about specific people.

Many students question the effectiveness of these new policies set in place.

“I feel like, with any social media platform, cyberbullying is bound to happen in some form, and it is pretty hard to identify and regulate,” said Wyatt Sauer, a sophomore business major. “With Yik Yak posting being completely anonymous, I feel like harassment is much more prevalent and harder to prevent, no matter what measures you have in place,” he said.

Most common are posts targeting individuals and those affiliated with Greek life. There are also posts that spread rumors about individuals using first and last names. Sororities and fraternities are subject to name-calling, criticism and harassment.

One user posted, “least favorite sorority … go,” which was followed by multiple comments naming sororities on campus.

“The app allows for cyberbullying in a way that hasn’t been seen before at TCU. Although entertaining, this app can hurt individuals’ feelings when their names are mentioned,” said Lauren Chavez, a sophomore strategic communications major.

But there are no usernames, no real names, no accounts and no profile photos of those posting.

“In high school, similar apps were used that were banned,” Chavez remarked. “I believe that same thing will happen here at TCU eventually – it’s just a matter of time.”