On Monday, Gov. Greg Abbott signed into law the newly-drawn map of congressional districts, finalizing the design of electoral maps in Texas for the next ten years.

In November of last year, the Republicans earned 53% of the vote in congressional races, but they now have control of 24 out of 38 seats held by Texas in the U.S. House.

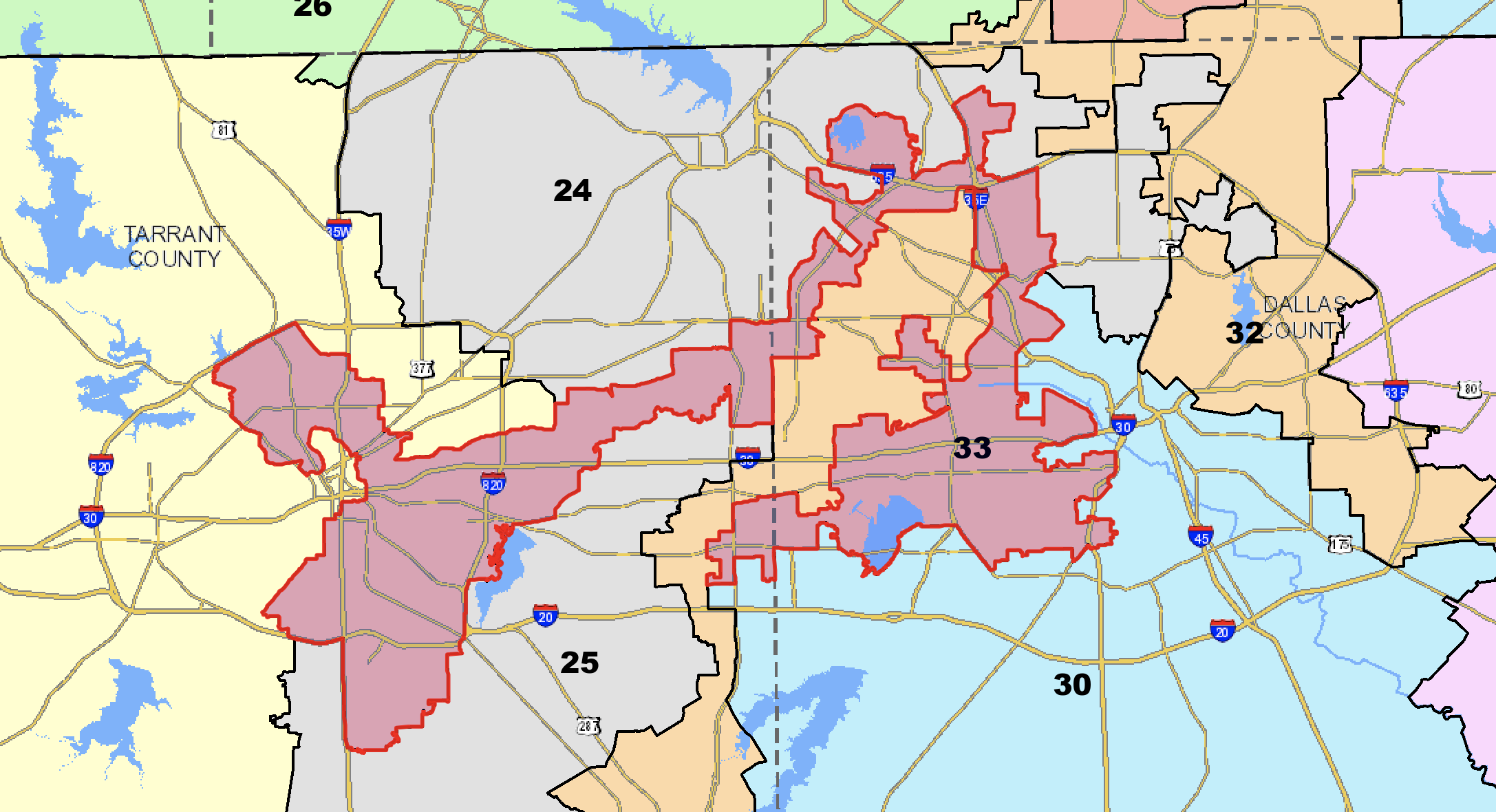

Critics say that it deliberately suppresses the votes of minority groups despite the fact that 95% of the population growth in Texas was from people of color; that population growth is what earned Texas two new seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, but the map puts both new districts, one in Austin and the other in Houston, under the control of white voters.

Rep. Yvonne Davis, a Democrat from Dallas, said in an interview that the GOP is trying to “erase African Americans and Hispanics from the state by not allowing them to have access to vote for a person of their choice.”

State Sen. Joan Huffman, one of the Republicans in charge of drawing the maps in the Senate Redistricting Committee, insisted that the map was “drawn blind to race.”

The map has already been challenged by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and lawsuits from other civil rights groups are expected to follow. However, in 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering wasn’t within the jurisdiction of the courts; just one month later, a different court said that Texas did not need oversight in the redistricting process that would have aimed to prevent racial gerrymandering.

Joanne Green, a political science professor at TCU, said that it’s important for people to understand gerrymandering because it can diminish both “the ability of voters to hold elected officials accountable” and “the competitiveness of elections.”

The word gerrymander was first used in 1812 in a political cartoon by Elkanah Tisdale in the Boston Gazette. The governor of Massachusetts at the time, Elbridge Gerry, had approved the state’s map with a district that Tisdale illustrated to look like a salamander in his cartoon. He captioned it “Gerry-mander,” and the term became popular.

After the census is taken every ten years, the number of seats in the U.S. House is reapportioned among the states based on population changes. Then, each state’s legislature redesigns its congressional district to reflect the new numbers. When the process becomes partisan, it is referred to as gerrymandering. The party holding the majority in each state’s legislature will get to design the state’s districts to its political advantage.

There are two methods of gerrymandering: cracking and packing. In cracking, Party A, which holds the majority in a hypothetical state, would look at the demographics of the state and try to dilute the political impact of Party B’s voters by carving up neighborhoods into different districts to prevent them from having a majority in as many districts as possible.

In packing, Party A would try to put Party B’s voters into as few districts as possible to try to give it as few congressional seats as it can. Legally, every district in a given state has to be as close to equal in population as possible, so there are some limits on the redistricting processes, but this rule certainly does not prevent blatant partisan gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering can have consequences for “our Constitutional structure, separation of powers, checks and balances…fundraising, and how much money is spent, and the role of interest groups, and the lack of competition in elections and what that really means,” Green said. “I don’t think people really connect all those dots, which is really quite unfortunate.”