Computer science students developed an app to make museum learning at TCU more accessible for visually impaired visitors.

The Oscar E. Monnig Meteorite Gallery in the Sid Richardson Building is home to one of the nation’s premier meteorite collections. Before COVID-19, the gallery saw as many as 10,000 visitors each year.

However, the gallery remained mostly unchanged since it opened in 2003, and its curator realized many of the exhibits needed to be more inclusive.

“All of that came to a head for me about three years ago and I thought, we are not offering an accessible gallery,” said Rhiannon Mayne, the collection curator and associate professor of environmental sciences at TCU. “If you think about if you are visually impaired […] coming into a gallery that’s all text and objects to look at, what can you take away from it?”

That’s where Bingyang Wei, assistant professor of computer science at TCU, came in.

Wei teaches senior design, a capstone course in the computer science department where students develop software-based solutions for real clients from Toyota to Fort Worth’s Mercy Clinic.

Each fall, he invites clients to come to campus and pitch their projects for students, who then select teams and work on their projects through the spring. Some students are focused on developing their skills in the industry, said Wei, “But also, some students, they have this enthusiasm about contributing back to the community.”

In the fall of 2021, Mayne presented a proposal to senior design students about improving inclusivity in the gallery through an app for visually impaired visitors.

Mayne and Wei said several students approached them afterward because of their interest in working on the gallery project.

“The first time that [Mayne] showed us, I was like, ‘I really like this project,’ first of all because meteorites! Like, who doesn’t like outer space falling on the Earth?” said Aparajita Biswas, one of the senior computer science majors who developed the app. “The thing that really got me was the accessibility part where it’s more accessible toward people with visual disabilities […] I just thought that was a great project.”

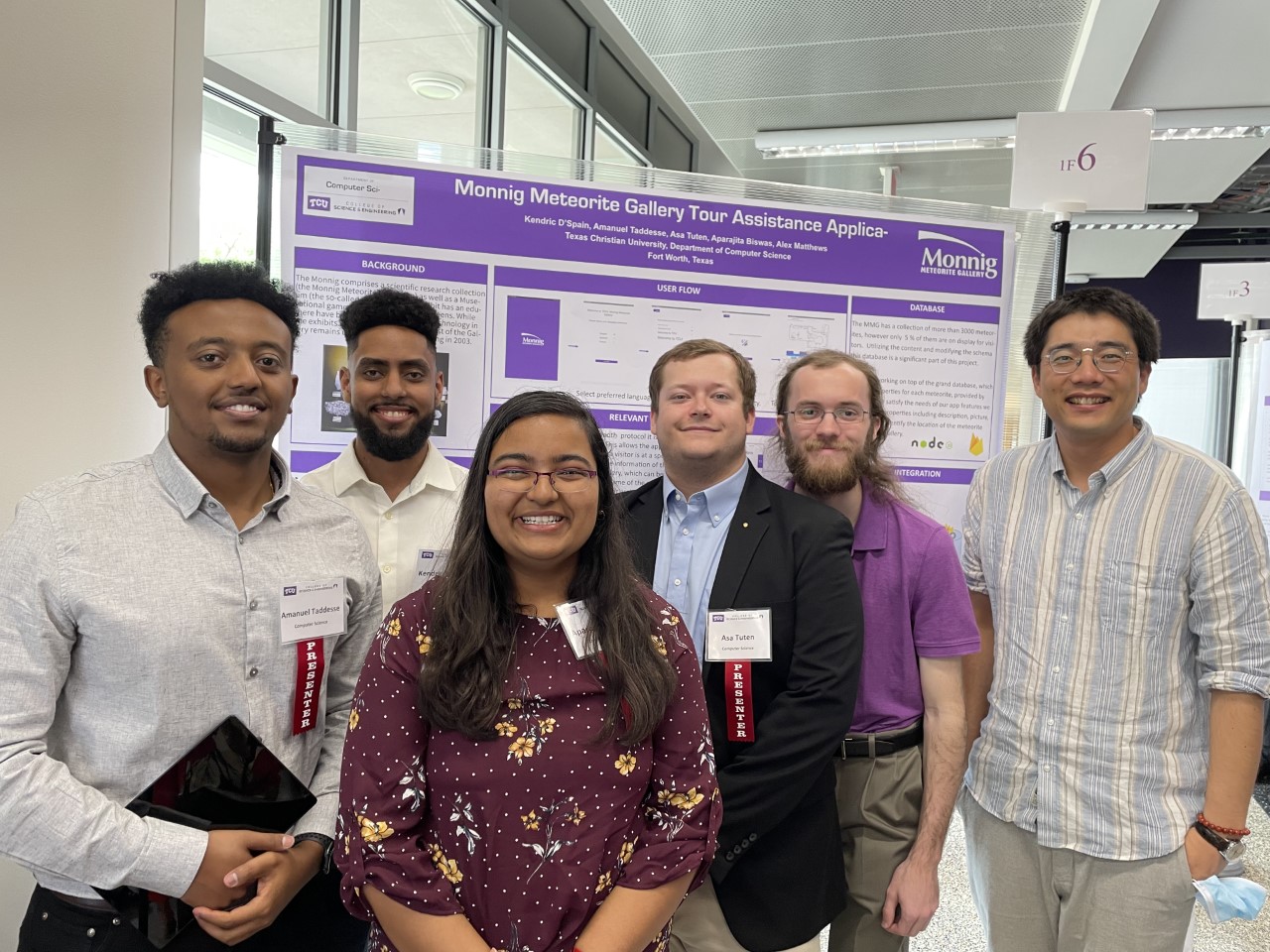

Biswas, Kendric D’Spain, Alex Matthews, Amanuel Taddesse and Asa Tuten formed a team to work on the project.

Unlike other senior design groups, the students could walk across campus to meet with Mayne weekly to discuss their progress and receive feedback, which helped them make changes in real-time.

However, Wei said the biggest benefit was how Mayne’s goals aligned with the values of the students.

“I think it’s a really good match, so our TCU students and our department can contribute back to the community,” said Wei.

Creating inclusivity in the gallery

Many students are unaware that in the realm of planetary science, TCU is out of this world.

When Fort Worth native and entrepreneur Oscar E. Monnig died in 1999 at age 96, he left his entire estate to the university – including his collection of 392 meteorites that was his life’s passion.

When Mayne joined TCU in 2009 as the gallery’s first paid curator, the collection had grown to 1400. Now, TCU is home to nearly 2,500 meteorites, one of the largest university collections in the world.

Only about 5% of the meteorites are on display, while the rest are part of a scientific collection that can be loaned out to other researchers across the world, said Mayne.

As a professor and curator of the gallery, Mayne splits her time between teaching, research and public outreach. On any day, you might find her leading kindergarteners through the halls of the meteorite gallery, explaining the impacts of climate change to first-year students or conducting research on TCU’s meteorite collection.

A planetary scientist by trade, Mayne is also passionate about science education. She said many people learn best from what she calls “free choice education,” where they can choose to learn about topics that interest them.

However, it wasn’t until she took a course on learning in the museum environment that Mayne understood the educational barriers the gallery posed to visitors.

“What struck me about that was if you’re not able to read, then you don’t get much out of the gallery,” she said.

The text-heavy exhibits could exclude young visitors, people who speak English as a second language and individuals with visual impairments.

Mayne said the course and her personal experiences “opened my eyes” to the importance of IDEA, or Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility, in the classroom and in the gallery.

Mayne has made it her mission to incorporate IDEA into the gallery – and the senior design students have jumped on board.

“Helping individuals with learning content or in any way possible, like through an app or just a certain teaching technique a teacher would use, I’m all pro for that,” said D’Spain.

Building the app

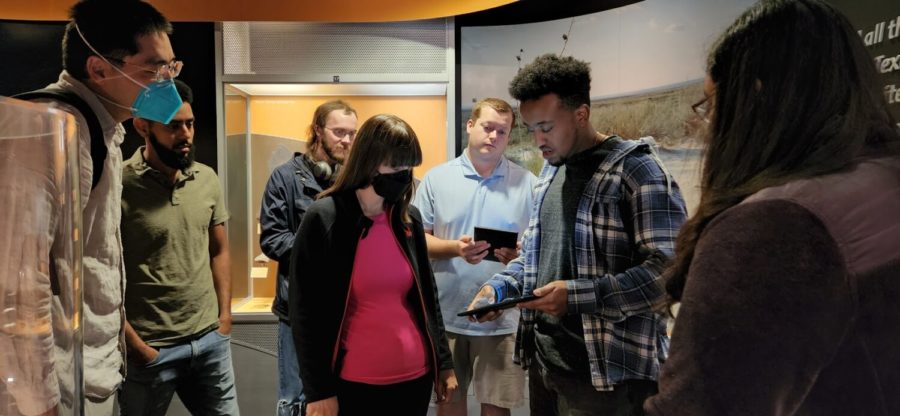

The students walked the gallery and discussed their ideas for improving accessibility with Mayne.

“It’s really old, like it hurts your eyes to look at some of the things […] like I can see any older person if they were going through there, they would not be able to understand and comprehend some of the things just because of how it’s presented to you,” said D’Spain. “What we have so far, it’s like, wow. It’s a big difference.”

The senior design group developed an app that can be downloaded onto tablets in the gallery for users.

The app includes features that will change the brightness, increase the font size, adjust for colorblindness or show visuals in dark mode. Visitors can also use the “text to speech” feature to read descriptions of the meteorites aloud or translate the text into Spanish, French or Vietnamese.

Users can search the museum meteorite catalog for specimens based on the item’s name, type and other categories. The tablets are connected to beacons set up across the gallery to pinpoint the user’s location and send information on the closest displays.

Taddesse said one of the biggest challenges was finding examples they could use as models for the app.

“A lot hasn’t been done yet on making apps accessible to visually impaired people,” he said. “We went to look at other projects that had been done to inspire us, but the problem was there hadn’t been enough done on that.”

Now, the students are becoming models themselves. The senior design team presented its work at the Student Research Symposium on April 22 and helped Mayne craft an abstract for a conference led by NASA on Advancing IDEA in Planetary Science.

After they graduate, team members may consult on the app to help the next group of students improve it and add more features.

The app will be launched in the gallery in the coming months.

“I’m excited to see how this actually plays out and I hope people enjoy it and see all the hard work we did,” said Biswas.

Next steps

The app may be complete, but Mayne is far from finished with improving the gallery’s accessibility.

“This should be the expectation,” she said. “I’m hoping this is just the start. I’m excited by it just because of the possibility that’s there and being able to offer a better experience for everyone who comes into the gallery.”

Next on her list: developing an ASL tool to help deaf and hard of hearing people tour the gallery.

“Especially the mother side of me, I want every child who comes in here to take something away with them and not feel like this was something designed to exclude them,” she said.

Wei said he would welcome the opportunity for senior design to partner with Mayne on gallery projects in the future.

Mayne is a responsive and accessible client, he said, but her work’s appeal extends beyond convenience.

“I tell my students, ‘Think about this, this is a legacy,’” he said. ‘Even after you leave TCU you can hand this over to the next generation of students so they will pick up this project and improve it, but your name will always be on there, so be proud of yourself!’”

After watching the students’ final demo of the app, Wei smiled. “I think they’re really making a difference,” he said.