Art and ecology collide in TCU’s zoo enrichment course

It started with a child’s question.

“There was a daughter of a former student who came in and asked me if I ever made toys for elephants in my classes,” said TCU studio art professor Cameron Schoepp. “Her father explained that they had watched a video of a professor from the east coast who occasionally teaches a class called ‘toys for elephants.’’’

The “toys for elephants" video that started it all. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

The “toys for elephants" video that started it all. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

“That intrigued me, and I had also previously worked with environmental studies on a prior project. I went to the chairman and said that this would be a fun class to co-teach,” he said.

This year marked the fourth time that Schoepp and ecology professor Tory Bennett have taught Zoo Animal Enrichment at TCU.

Throughout the course, students explore the ecological behavior of wild animals to gain insights into the types of stimuli that they encounter naturally. Next, they develop and build structures meant to engage and enrich the lives of the animals at the Fort Worth Zoo.

Once Schoepp and Bennett landed approval from the chairperson, the next step was for them to figure out how they could make this class happen. They both wanted to find ways to make it more than just creating objects for the zoo.

“We tried to figure out a way it could be more science-based,” said Schoepp. “The students do ecological studies on the animals by studying their behavior and particular needs.”

“We try to create something that allows the animals to use the natural behaviors that up until now, they haven't been able to use,” said Bennett.

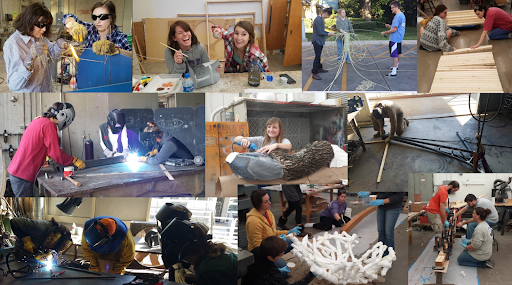

The professors have the students work in teams to study a specific species at the zoo and create objects that will enhance their lives in captivity.

“This wouldn’t work if we didn’t have the art students combined with the ecology students,” said Bennett. “You can make all sorts of things and put them in the zoo, but if you don’t have a background in ecology, you can’t possibly design something that will be that effective."

Bennett shows a powerpoint to the students as an introduction into the course. This slide shows the students that teamwork is necessary for a successful project. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

Bennett shows a powerpoint to the students as an introduction into the course. This slide shows the students that teamwork is necessary for a successful project. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

“Same goes for the ecology students - they can’t weld to save their life,” she said. “They couldn’t come up with these ideas. That combination and collaboration makes it work. It is an example of how you need every aspect of art and science to solve world problems, or in this case, zoo enrichment.”

Bennett and Shoepp have taught this class four times so far, recruiting graduates and undergraduates to take the course.

“We draw from a pool of students who have completed certain prerequisites and would work well with this particular group,” said Schoepp. “We encourage them to take the class, because we can’t necessarily make them sign up.”

Both professors assess their students’ personalities, strengths and weaknesses to determine the perfect group of three.

“We have teams of three: one advanced ecologist, one advanced artist and a little wiggle room for either-or, or a newbie,” said Bennett.

Once the teams have been established, there is a whole semester's worth of work to be completed in time to be installed in the zoo.

“The final pressure is on because the final product becomes a part of the zoo and is in contact with animals so you can't fail,” said Schoepp. “You have to create something that is going to work, safe for the animals and does its job. We push them very hard to perfect these things.”

“We are held accountable because they can't half-do anything,” said Bennett.

“The zoo won't use it if it doesn't meet the criteria,” said Schoepp.

Throughout the years, the duo has seen projects that have held up and others that have fallen apart once installed at the zoo. One year a group of students created a beaver dam that could be used by otters at the zoo. The professors said the student's structure didn't last very long.

Otters enjoying their new beaver dam built by TCU students at the Fort Worth Zoo. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

Otters enjoying their new beaver dam built by TCU students at the Fort Worth Zoo. (Photo courtesy of Tory Bennett)

“The otters will use beaver dams as shelter,” said Bennett. “The otters loved it to death within a few days. The materials that the students used did not take into account how playful and strong otters are.”

“There is all this problem solving that has to happen when you introduce something into their environment,” added Schoepp. “Will they swallow something that hurts them? Will they be able to pick up things and throw them at people? Is it safe for the zookeepers or the audience that's visiting?”

Adaptability has been a key element throughout the years. The duo has learned from the failures of others to help promote success among their students. However, their favorite part about teaching the class is not the finished product, but how the animals react to the new object being placed in their enclosures.

“What they do is they put the objects into the enclosure and then they release the animals into the enclosure,” said Bennett. “It gives the students the chance to explain what they have created and say what they have aimed for and hope to see then they release the animals. Every time the animals run out and do exactly what they are supposed to.”

Creating the object may seem like the easy part, but the real challenge comes from picking the animal and choosing what to construct. Once the professors have established the groups for the semester, they send them to the zoo to scout the animals. They tell their students to choose three animals that appeal to them and to find background with supporting data about each one.

“If they can't find information on the animal, we say chuck it,” said Bennett. “We can't do anything or decide what it needs if it doesn't have that scientific information. It all comes down to which one has the most and what you can work with.”

Once the students have decided on the animal they want to focus on, the next step is creating an animal profile. Their profiles are aimed at addressing the basic needs of their animal: what environment they live in, how they get food and find water, what their social groups look like, their mating habits, how they build shelter and more.

“Slowly but surely, the next stage is that once we know all these things, what can't they do at the zoo?” said Bennett. “The next step is to identify those behaviors and how we can recreate them.”

This semester, the class had three teams that tackled unique animals with different behavioral patterns.

This year's groups

Group 1's 3D printed mold macaw feeder. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

Group 1's 3D printed mold macaw feeder. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

Group 1: Senior environmental science major Gloria Serrano and Master of Fine Arts graduate students Benjamin Loftis and Madi Ortega focused their efforts on the Hyacinth Macaw, a stunning cobalt blue bird with yellow coloring around its eyes and the base of its beak. It is the largest parrot in the macaw family.

“We saw that she didn’t have the ability to apply her full strength with her beak,” said Serrano. “Everything that was given to her, she destroyed.”

The group decided to create something that would make the macaw work for her food instead of just having it placed in her cage.

“Our idea is to not only create something that is sturdy for her, but also something that challenges her food acquisition,” Serrano said. “This forces her to manipulate something in order for her to receive an award and really allows her to attack it.”

Their creation looks like a chandelier. Food is placed inside the top where it spills into different places within the structure where the bird has to retrieve it. The structure was made out of 3D plastic, then printed and waxed into form. The group planned to dip it in wax and finally cast it in aluminum.

“It is designed so that everything inside allows her to use the full force of her beak,” said Serrano.

Group 2: Lauren Griffin, a senior combined science major, Nathan Little, a senior sculpture major and Sydney Martin, a junior studio art painting major, focused on the gray fox. They are sometimes known as the “tree fox” or “cat fox” because it is one of two species of canid that climb trees. Their rotating wrists and semi-retractable claws allow them to climb high to den, forage or escape predators.

Nathan Little is building Group 2's jig. The jig is going to allow them to consistently cut PVC pipe. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

Nathan Little is building Group 2's jig. The jig is going to allow them to consistently cut PVC pipe. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

Marshall, the gray fox at the Fort Worth Zoo, has an indoor and outdoor enclosure.

“On the outside, he didn’t have anything where he could use his natural abilities to climb trees,” said Griffin. “Gray foxes forage in trees in the wild. They like to evade predators and play using trees. Trees are just a huge part of their natural instinct in the wild.”

The group wanted to maximize the enclosure vertically. Marshall’s enclosure isn’t large, but the group felt that they could double the space by making it vertical.

The group decided to make a tree out of PVC pipe and rubber. The textured rubber looks like tree bark. Marshall will be able to sink his claws into it and climb to the top.

“The zookeepers can also put food up there so there is a reason for him to climb the tree,” said Griffin. “He is going to mimic these natural foraging habits by climbing these trees to get food.”

Group 3: Lane Rosal, a sophomore sculpture major, Davion Mack, a junior sculpture major and Taylor Craig, a senior environmental science major, worked with the Patagonian Mara, a large rodent with the long ears of hare and a body that resembles a small deer. It has long, powerful hind legs which allows it to rapidly escape from predators and four sharp claws that allow it to burrow.

Group 3's 3D model of their feeder for the Patagonian Mara. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

Group 3's 3D model of their feeder for the Patagonian Mara. (Sara Littlejohn/Staff Writer)

“In his natural habitat, he would go around from place to place and graze with his species group,” said Rosal. “He doesn’t have anything like that in the zoo because he is in a small offsite enclosure with concrete flooring.”

He was being fed from a dog bowl so his access to food was very immediate – much different from foraging in the wild.

“We are trying to create a feeder for him that’s very similar to a snuffle mat for dogs,” said Rosal. “It would encourage him to actually search for food as he would be in the wild. It would also encourage him to move from spot to spot like they do in the wild.”

The group used a fire hose as the main component of the structure. They are also using two-part animal-safe epoxy to encompass the structure.

“Since he is a rodent, his teeth are constantly growing,” said Rosal. “He is always going to be chewing on things so we wanted to choose a material that would be durable for him, and exercise the natural tendencies that he has.”

Aftermath

All three of the group’s structures were dropped off at the Fort Worth Zoo on the evening of April 28. Each group presented their structure to the zookeepers. After each presentation, their work was installed into the animal’s enclosure. The animals were then released to interact with their new structures.