TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative paves the road to reconciliation

The Brown-Lupton University Union Auditorium felt heavy.

Dr. Gregg Cantrell, Erma and Ralph Lowe Chair in Texas History, began sharing examples of racism found in TCU’s early 1900s student publications.

In 1917, TCU’s yearbook editors included an image of the all-black kitchen staff in the ‘student organizations’ section of the yearbook, “facetiously calling them the culinary club,” said Cantrell.

The silence that previously filled the room was interrupted by quiet gasps of shock from the crowded auditorium.

Cantrell showed the 1917 yearbook photos of black TCU employees, Joe Allen and Arthur Hunter. Printed next to Allen’s name is the name, “Old Negro Joe.” Hunter was called, “Blackie.”

More gasps followed.

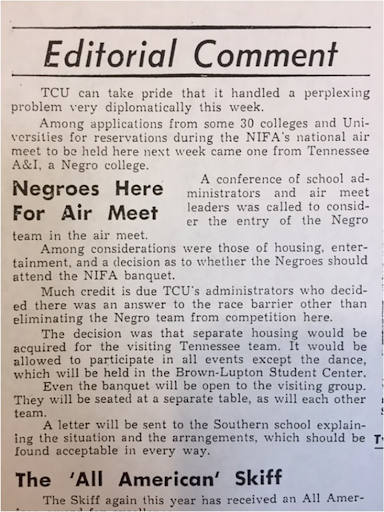

Cantrell shared some of the early articles published in TCU’s student-run newspaper, the Skiff. Excerpts from stories riddled with racist language were displayed on the screen.

Student journalists explain their support for part segregation, part desegregation, when TCU hosts a Black competition team in 1955. (Skiff, April 29, 1955.)

Student journalists explain their support for part segregation, part desegregation, when TCU hosts a Black competition team in 1955. (Skiff, April 29, 1955.)

Blackface cartoons, racist jokes, and uses of the “n word,” were all a part of the Skiff’s 1900s publications.

The room was in disbelief.

These stories were shared during TCU’s second annual Reconciliation Day event, a day to acknowledge and reconcile TCU’s history with slavery, racism, and the Confederacy.

“You can't go somewhere if you don’t know where you’ve been,” said Chancellor Victor Boschini in his closing remarks.

This idea is central to why TCU’s race and reconciliation initiative created Reconciliation Day, a day to highlight aspects of the university's history that are often forgotten about. Their mission is to embrace the past, rather than erasing it, in order to reconcile and continue to move forward from TCU’s racist roots.

Part of reconciling the past is acknowledging the many Black individuals who were instrumental in the success of the university in its early days. This year, formerly enslaved couple Charley and Kate Thorp were recognized at the event.

TCU’s Add-Ran Male and Female College was first established by Pleasant Thorp in 1854. In 1855, Pleasant Thorp brought two enslaved people to the campus location in Thorp Spring: Charley Thorp, who was seven at the time, and his mother. Thorp later married Kate Lee in 1882, whose mother was formerly enslaved by the family of Randolph Clark’s wife.

Photograph of Add-Ran College in 1890, when it was located in Thorp Spring (Photo courtesy of TCU RRI)

Photograph of Add-Ran College in 1890, when it was located in Thorp Spring (Photo courtesy of TCU RRI)

Kate did laundry for Randolph Clark’s family, worked in the community as a nurse and midwife, and helped college girls with various tasks. Joseph Lynn Clark, son of Randolph Clark, described Charley Thorpe’s labor for TCU as including “practically every detail, aside from academic activities, not specifically belonging to someone else.”

Cooking, cleaning, caring for sick students, and maintenance work were all responsibilities held by Charley and Kate.

Despite their essential role on campus and their hard work, the Thorp’s were denied a formal education. Their efforts weren’t more than a footnote in TCU’s history. Everything they did for TCU, was almost forgotten.

Almost.

Due to the RRI research team’s findings, Charley and Kate are finally being given the recognition they deserve. Acknowledging their story was especially impactful at this year's Reconciliation Day event, as over 30 of Charley and Kate’s living descendants were located and in attendance.

History lives on through the lives and stories of people still walking the earth today. Despite how long ago the Thorp’s made their impact on TCU, their descendants are proof that, “it’s still something we’re connected to,” said Dr. Frederick Gooding, chair of the race and reconciliation initiative.

Loriessa Randle’s voice shook as she held back her emotions in a video interview with TCU. Randle, a descendant of Charley Thorp who attended Reconciliation Day, said that after reading about everything Charley Thorp did for TCU, she just wants his story to be acknowledged.

“I really want people to know that he was a human being,” Randle said.

Another descendant of Charley and Kate, Debra Duncan Holmes, expressed her gratitude to have played a part in recognizing Charley Thorp.

“It took 170 years to recognize this man, but it happened for him. And I’m glad because I was a part of it. I was part of putting the puzzle together,” said Holmes.

The Reconciliation Day program concluded by awarding the descendants of Charley and Kate Thorp with the Plume award. Engraved on the large plaque reads: “May we remember, respect, and reconcile, the living legacy of Charley and Kate Thorp.”

A bigger initiative

This event was just one part of a much bigger initiative. TCU’s race and reconciliation initiative is a five-year study that began in July 2020. Provost Teresa Abi-Nader Dahlberg appointed a 28-member committee to research TCU’s history by uncovering documents and artifacts to share with the public.

Now in year two of their study, much of the group’s time has been spent compiling a first year survey report. This report divides TCU’s history into three windows of time: “The Founding Years,” 1861-1891; “Transition to Integration,” 1941-1947; and “Recent but Related Histories.”

RRI’s central research question for the “Founding Years” asks: How did the institution of enslavement affect TCU’s identity formation? This section of the report sets the scene for the historical context surrounding the years in which TCU was founded.

Dr. Frederick Gooding Jr. speaks during the Race and Reconciliation event last year. (Esau Rodriguez Olvera/Staff Photographer)

Dr. Frederick Gooding Jr. speaks during the Race and Reconciliation event last year. (Esau Rodriguez Olvera/Staff Photographer)

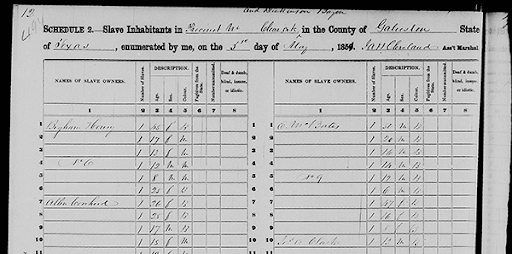

Students are often taught that enslavement wasn’t a major part of Texas history compared to other slaveholding states to the east. Yet historians continue to find evidence of the prominence of enslavement in Texas. According to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission, an 1860 census found that slaves accounted for over 30% of the total population of Texas.

TCU was founded as a direct reaction to the destruction brought about by the Civil War. However, the survey report ultimately found that the university “had little direct connection to either enslavement or the Confederacy,” and that enslaved Black labor “did not contribute substantially to the creation of the university.”

Although the university as a whole may not have had a direct connection to enslavement, records show that Joseph Addison Clark, the father of TCU’s founders Addison and Randolph Clark, owned a slave in 1860, valued at $1,000. Addison Clark also served as a Confederate officer, and was joined by Randolph Clark at the end of the war, though not enrolled as a soldier.

“United States Census (Slave Schedule) 1850” (Courtesy of TCU RRI) Transcription from line 10, right side: Jos A Clark, number os slaves 1, age 13, Male, Black

“United States Census (Slave Schedule) 1850” (Courtesy of TCU RRI) Transcription from line 10, right side: Jos A Clark, number os slaves 1, age 13, Male, Black

After looking at how enslavement and the confederacy impacted the founding of TCU, the RRI survey report shares findings from the “Transition into Integration” period. They focused on answering the question: How do systemic racism and discrimination continue to manifest?

The report found that “several decades before TCU’s entire campus officially desegregated, a very small number of Black students had partial access to a TCU education.” During World War II, TCU provided background training for naval and marine officers and pilots. A select few blacks who were in the military could enroll, but only in the Evening College.

In the mid-1900s, The Skiff periodically published information about how students felt towards segregation/desegregation. In a 1952 poll, 75% of students favored non-segregation. However, five years later, a separate student survey revealed that more than half of students favored maintaining segregation.

Over the next roughly ten years, TCU’s individual campuses would slowly begin to desegregate, before the TCU Board of Trustees ultimately voted to racially integrate the full campus in 1964.

However, TCU often addressed the issue of integration with a sense of caution and reluctance, making it a slow moving and difficult process. The RRI survey report quotes President Sadler, who in 1951 acknowledged that: “For the past ten years, we have wanted to avoid any action which would cause any people to point to us and say ‘Texas Christian University is pioneering and pushing out in the matter of non-segregation.”

By the 1970s, things seemed to be improving for Black students at TCU. In 1971, photos of Black students were featured throughout the TCU yearbook. This included Jennifer Giddings, the first Black woman to be voted Homecoming Queen both at TCU and in the entire Southwest Conference.

Yet were things really improving? If you flip a few pages in the same 1971 yearbook, members of Phi Kappa Sigma can be seen holding a large confederate flag. Despite the university being fully integrated, racism and discrimination were still a large part of the campus culture.

TCU still wasn’t the most welcoming environment for black students.

Later that same year, TCU student Frank Callaway said in the Skiff that, “TCU still treats its Black students like visitors, not like the school belongs to them, too. The university tolerates us. They try to keep us from being angry. But we still feel like we’re being short changed.”

The final aspect of the RRI survey report examines “Recent but Related Histories.” In this section, the group shares their goal to diversify TCU’s vendor list by including more businesses operated by Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color.

The findings provided in the report make it clear: there is no hiding from the institutionalized racism found throughout TCU’s history.

“As an academic institution, it’s also important for us to explore, examine and acknowledge the completeness of TCU’s story, which began during a time of painful strife, incredible innovation and dynamic growth,” Chancellor Victor Bochini said in the opening note of the survey report.

Homescreen of TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative webpage

Homescreen of TCU’s Race and Reconciliation Initiative webpage

As a part of the university’s goal to tell the honest and complete story of TCU’s history, TCU joined Universities Studying Slavery, a group of higher education institutions that share resources and dedicate themselsves to telling the whole story. Other universities involved include Brown University, Georgetown University, Harvard University, and a handful of others.

TCU’s race and reconciliation initiative hosted over 90 programs just in their first year, but they have no intention of stopping there. TCU acknowledges that reconciliation is an ongoing process, and that they are committed to continuously improving diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus.

Aisha Torrey-Sawyer, director of TCU’s diversity and inclusion initiatives, said the group is already planning to meet in the summer to discuss how to add to the Clark brothers statue in order to tell a more complete story.

Without the efforts of the RRI, Charley and Kate Thorp’s story might have never been told. The struggles black students faced might have gone unacknowledged. The painful history of segregation and descrimnation on TCU’s campus might have been forgotten.

But their stories have finally been told. Their struggles acknowledged. TCU hasn’t forgotten.

And because TCU hasn’t forgotten, the path has been set for a long and never ending road towards reconciliation.