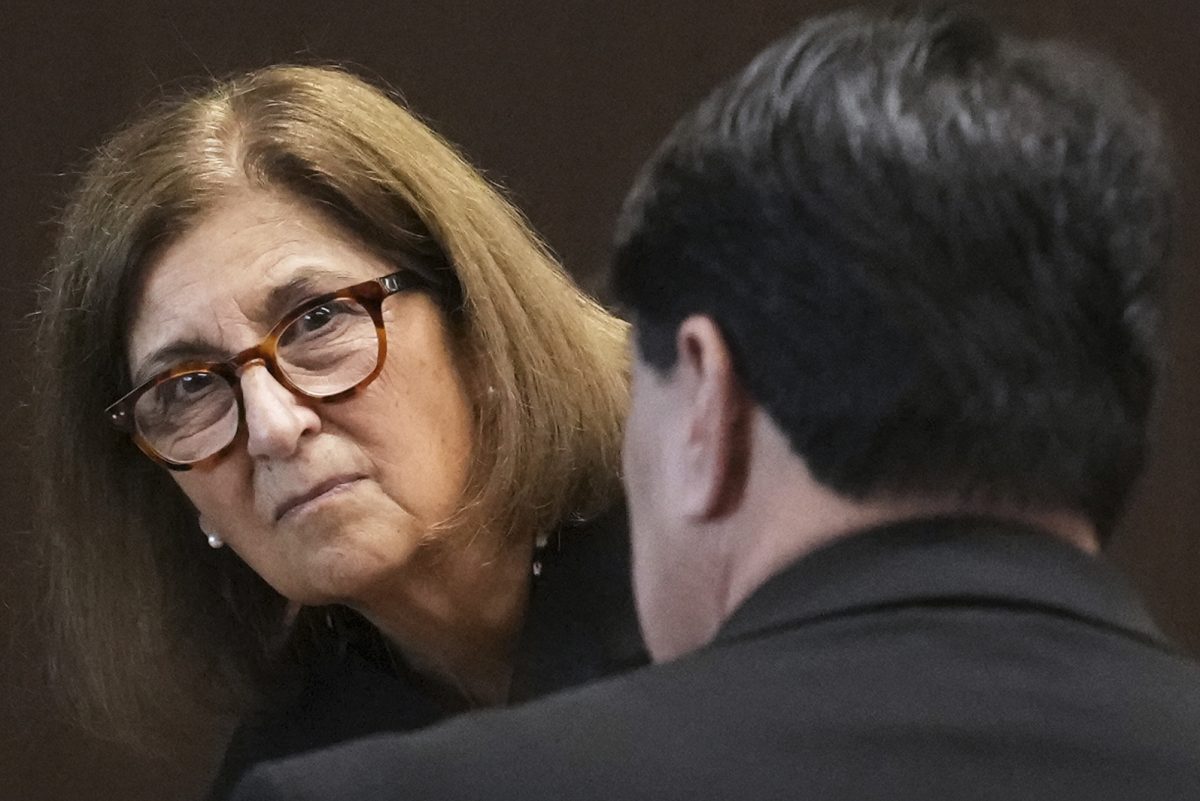

Julia Pughes, formerly known as Yu Lian Qing, described her life as a mystery – a mystery rooted in her abandonment as an infant at an orphanage gate in China.

Pughes, now a kindergarten teacher in Rockwall, Texas, was adopted in 2001 during a time when strict family planning measures limited most Chinese families to having just one child. Implemented in 1979 to curb rapid population growth, these policies had a profound impact on Chinese society.

The one-child policy in China aimed to control rapid population growth amid concerns about resource shortages and economic development. Families were limited to one child; however, China did have exceptions to this policy for ethnic minorities and rural families whose first child was a girl. Enforcement included fines, sterilizations, increased monitoring and surveillance of women, forced abortions and more. This would impact China’s demographics and society, particularly by contributing to a gender imbalance due to a cultural preference for sons, resulting in millions of “missing women.”

Criticism of the one-child policy increased over the decades, focusing on human rights violations and social repercussions. By the early 21st century, the government recognized the challenges of an aging population and a shrinking workforce, according to research by N. Renuga Nagarajan and Andrew Sixsmith.

In 2015, the one-child policy was replaced by a two-child policy. It was then raised to the three-child policy in 2021, according to Human Rights Watch. This change aimed to encourage population growth and address demographic challenges, including a declining birth rate.

Julia’s mystery

Pughes was adopted when she was 11 months old after being abandoned at the gate of an orphanage in Yujiang County, a district of the city of Yingtan, Jiangxi province, China. Pughes was left with no note or any ability to connect herself with her birth parents. She has spent some time pondering over potential theories surrounding her abandonment. She believes that she was abandoned due to China’s one-child policy and often questions her birth parents’ motives behind abandoning her.

“My own theory I wonder about is that I could possibly have an older brother that I have no idea about,” Pughes said.

The policy negatively impacted China’s female population, who were discriminated against and were often disproportionately aborted or abandoned, according to The National Library of Medicine.

In a research database published by the Journal of Economic Behavior, it was found that between 1950 and June 2018, there were “16,969 child abandonment reports and 24,175 child abduction reports filed by the families of missing children” in China. The number of reported missing children shows a clear rise and fall pattern, increasing more than nine times from its pre-1979 level during the rapid economic growth period of the 1980s and 1990s, according to the journal.

“In China, they loved the boys because they could hold the surname, they can take care of the family because they move in with them after they’re married,” Pughes said. “So, all of these baby girls were being given up for adoption, because at that time, girls didn’t really have any value. So, you had a ton of girls in the orphanage.”

The larger picture

Pughes’s story is not particularly unique within the realm of China’s one-child policy.

“They’re not unique cases, which tells us that there are challenges across different locales, whether they’re rural areas or urban areas, high demand areas or less demanding areas,” Carrie Liu Currier, a professor of Asian politics at TCU, said. Currier described a common practice that occurred in the earlier stages of the one-child policy–concealing pregnancy.

Punishments for violating the policy led many to abandon their children.

“So, if you violated the policy by getting pregnant–if you had the child, whose responsibility was that if you don’t keep the child?” Currier said.

To manage and deter abandonment, government orphanages often restricted adoptions until children were about a year old, resulting in common adoptions at that age. The treatment in orphanages was often poor, with children left without interaction, leading to physical deformities.

“The concern was that if you knew you could give up your child to an orphanage, and they would go to some nice Western family, or they’d go somewhere and have a good life, well, that would not deter you,” Currier said. “The whole point was to try to deter people from having children, so this was a way to discourage people from seeing orphanages as an option.”

The adoption process at the time

Pughes’s adoptive parents, David and Krystal, began the adoption process in 2000. Her parents believe that adoption agencies encouraged international adoption from China at the time due to the large number of children needing to be adopted under the one-child policy.

“People would come up to them and just say, ‘lucky baby, lucky baby,’ because they knew that the babies were going to America and were going to have a better life,” Pughes said.

Her parents said adopting a girl made the process easier. Krystal recalls being told that they “could adopt a boy, but it took twice as long as no one ever gave up boys unless something was ‘wrong’ with them, since that was considered a disgrace to the family.”

David described the adoption process itself as challenging.

“We had to undergo medical testing to prove we were healthy and good, both physically and mentally,” he said.

The couple faced a mountain of paperwork and strict timelines, which often felt overwhelming, but they said it was well worth the effort. David and Krystal decided to adopt Mallory Pughes, Julia’s adoptive sister, two years later.

Lasting impact

Family dynamics changed significantly after the implementation of the one-child policy.

“This policy forced people to change how they view family,” Currier said. For example, the policy placed a heavy burden on the only children.

“Because there’s only one child, you have the four-two-one problem, which is where one child is responsible for supporting two parents and four grandparents, Currier said. “So, when only children marry, that’s sort of a big burden placed on family structures about their roles and the idea of extended family.”

Pughes’s story is one example of the effects of China’s one-child policy, which shaped both individual lives and societal structures. Her abandonment reflects broader issues of gender discrimination and family pressure. The policy’s impacts extend to China’s economic challenges and shifting family dynamics, as highlighted by Currier.

As China addresses the long-term effects, stories like Pughes’s demonstrate the wide impact of government interventions on personal lives.