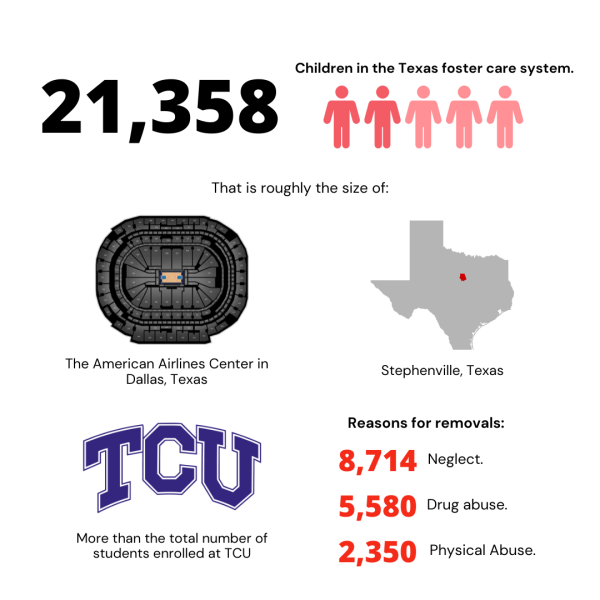

Texas’ foster care system is at a breaking point. Overcrowded shelters, exhausted caseworkers and a backlog of children without stable homes paint a grim picture of a system struggling to keep up. Federal and state courts are pushing for reform, and advocates are calling for urgent change. In response, Texas lawmakers are trying to find ways to mend the state’s broken foster care system before more children fall through the cracks. Legislation pending in Austin would make it harder for the state to sever parental rights in cases of abuse or neglect. The proposed change would alter the legal standard from reasonable efforts to active efforts. The shift in terms was met with resistance from some who argued the higher standard could delay necessary interventions, leaving children in unsafe environments for longer periods of time. However, supporters of Texas Senate Bill 620 expect this to prevent unnecessary family separations, ensuring the state exhausts all of the possible resources to support struggling parents before taking the extreme step of termination. Foster care is at the forefront of this issue. Any shift in policy regarding parental rights will have direct consequences on the number of children in foster care — either easing the burden or worsening the crisis.

At the same time, the system must also find placements for children with higher levels of need, including those who struggle with physical aggression or suicidal ideation. In many cases, these children — along with sibling groups and teenagers — are placed in residential treatment centers. “Those kids are typically placed in a more restrictive environment, often that looks like a residential treatment center,” Crockett said. “There’s always a shortage of staff for those facilities, and a lot of staff turnover happens.” High turnover rates in these facilities are often linked to inadequate funding, which limits resources, reduces staff pay and increases burnout among workers. The financial strain on the foster care system affects not only staffing but also the quality of care children receive. A combination of federal and state funds primarily supports Texas’ foster care budget. The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) was allocated $4.58 billion for the 2022 fiscal year. However, many advocates argue that current funding is insufficient to meet the system’s growing demands. “There are people in the field who talk a lot about it. You know, you can make the same hourly rate at Buc-ee’s as you can at a residential treatment center,” Crockett said. “And obviously, the work environment and the stress of the job is much harder. The pay isn’t high enough to keep staff in those jobs.” At its core, foster care is intended to provide stability, safety and support for the state’s most vulnerable children. But without adequate funding, better incentives for foster parents and improved working conditions for caseworkers and staff, Texas risks failing the thousands of children it is meant to protect.

At the same time, the system must also find placements for children with higher levels of need, including those who struggle with physical aggression or suicidal ideation. In many cases, these children — along with sibling groups and teenagers — are placed in residential treatment centers. “Those kids are typically placed in a more restrictive environment, often that looks like a residential treatment center,” Crockett said. “There’s always a shortage of staff for those facilities, and a lot of staff turnover happens.” High turnover rates in these facilities are often linked to inadequate funding, which limits resources, reduces staff pay and increases burnout among workers. The financial strain on the foster care system affects not only staffing but also the quality of care children receive. A combination of federal and state funds primarily supports Texas’ foster care budget. The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) was allocated $4.58 billion for the 2022 fiscal year. However, many advocates argue that current funding is insufficient to meet the system’s growing demands. “There are people in the field who talk a lot about it. You know, you can make the same hourly rate at Buc-ee’s as you can at a residential treatment center,” Crockett said. “And obviously, the work environment and the stress of the job is much harder. The pay isn’t high enough to keep staff in those jobs.” At its core, foster care is intended to provide stability, safety and support for the state’s most vulnerable children. But without adequate funding, better incentives for foster parents and improved working conditions for caseworkers and staff, Texas risks failing the thousands of children it is meant to protect.

Texas foster care crisis: Overcrowding, shortages and reform efforts collide

By Presley Walker, Staff Writer

Published Feb 10, 2025

Categories:

Texas’ foster care system is facing a crisis as overcrowded shelters and understaffed caseworkers struggle to meet the growing demand. With lawmakers debating crucial reforms, the future of thousands of vulnerable children is at stake. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel, File)

More to Discover