Lessons of perseverance

Two tragedies -- the Kent State Shootings and COVID-19 --have bookended his academic life.

Meet TCU’s outgoing dean of the AddRan College of Liberal Arts: Andrew Schoolmaster.

In 1970, during the aftermath of the May 4 shooting by Ohio National guardsmen, Andrew Schoolmaster finished his first year of college by mail.

Now the COVID-19 pandemic is forcing him to close his career as a professor and dean while working from home.

Protests against the Vietnam War reached a critical stage in the spring of 1970. Students across the country were protesting U.S. involvement. In the early afternoon of May 4, an estimated 3,000 protestors and spectators gathered on the campus Commons at Kent State to protest the expansion of the war into Cambodia.

They were met by the Ohio National Guard. At least 1,000 guardsmen had been sent to Kent, Ohio, by the governor in response to continued protests.

The crowd was ordered to disperse. It's unclear who ordered the guardsmen to shoot.

Schoolmaster was in a world history class. It was a 12 p.m. class; shots were fired 24 minutes later.

"All you could hear were sirens,” Schoolmaster said. “It just seemed like they wouldn’t stop.”

Four students were killed; nine lay injured.

Class was dismissed.

In the confusion, he tossed a few things into one suitcase and caught a ride home to Rochester, New York, with someone living down the hall. With police circling the campus and yelling into bullhorns, Schoolmaster said it felt like they were under martial law.

Within three hours the campus was vacant.

“Everyone knew that something terrible had happened, but no one had a sense of the magnitude,” Schoolmaster said.

He didn't learn the full story until he watched the evening news.

Among the dead was his friend and ROTC sergeant, William Schroeder.

Dr. Jerry Lewis was an assistant professor of sociology at Kent State, and an eye-witness to the shootings.

He was standing in the Prentice Hall parking lot, worrying about the National Guardsmen using their bayonets on the students.

They fired instead.

"My first thought was that the guard were firing at me," Lewis said. "That was how I was taught in the Army."

He dove behind the bushes for cover.

The Prentice Hall parking lot was where most students were killed or injured.

The shootings triggered a nationwide student strike, and many universities closed.

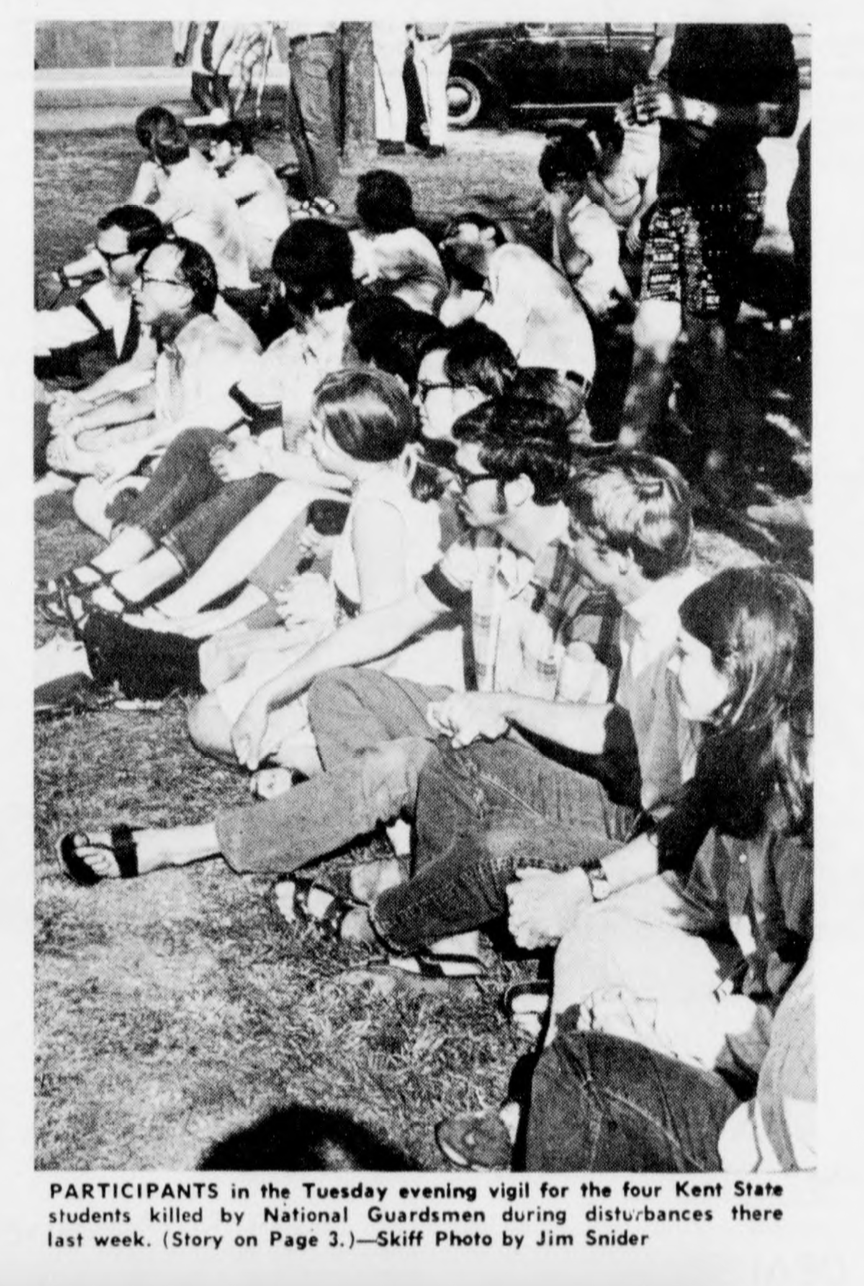

TCU stayed open, but students felt the impact.

On Tuesday, May 5, 100 students sat in a circle around Frog Fountain for a silent vigil.

They sat in silence, holding hands for 30 minutes in memory of the four Kent State students who were killed.

'Snail-mail'

Weeks later, Schoolmaster received a letter from Kent State.

To complete each of his courses, he had to write a two-page summary of each chapter yet to be covered in all of his textbooks. Then, he had to mail the summaries back to his professors.

“There was no Zoom, no internet, nothing,” Schoolmaster said. “Just snail-mail and the telephone.”

Lewis assigned his students the same task.

“We were given the addresses of the students in our classes,” he said. “We were told to contact them and come up with something.”

Lewis continues to teach at Kent State as a guest lecturer on the events of May 4.

The 'white-knuckle adventure'

Schoolmaster said students today have significant advantages.

They can communicate with professors through the internet and Zoom, a video-conferencing platform many TCU professors use to conduct classes remotely.

First-year speech pathology major Libby Warren recognizes this advantage, as well as the difficulties that still remain with online instruction.

“The professors have been so good with communication, but I think they are struggling as much as we are,” she said. “We’re all going through this change together.”

Schoolmaster calls it a “white-knuckle adventure.”

He learned that TCU would move classes online for the semester at a special meeting of the Provost Council on March 11. For the next two weeks, he led the college in the process of converting all courses online.

After 40 years as a professor, and 13 years as the dean of AddRan, he will retire this year with off-campus instruction once again.

But now his days are filled with emails and Zoom meetings instead of postage and ink.

“It’s a mixture of sadness and surprise,” Schoolmaster said. “This is just not how I envisioned the end of my career.”

This is not how TCU students envisioned the end of their semesters, either.

They left campus for spring break on March 7, expecting to return one week later.

“I knew about the coronavirus, but I never thought we wouldn’t be able to come back,” Warren said. “I was even excited when spring break was extended one extra week."

But once it was announced that students wouldn't be coming back, Warren found herself packing up her dorm room in Colby Hall weeks earlier than expected.

First year students Libby Warren and Taylor Kalahar in front of Colby Hall. Photo credit: Libby Warren.

First year students Libby Warren and Taylor Kalahar in front of Colby Hall. Photo credit: Libby Warren.

“We were just starting to make friends,” Warren said. “We were just starting to get comfortable with everything. Then it was just, like, over. But, I know it’ll work out so I’m looking forward to next semester.”

July, 1970

Schoolmaster wasn't able to clear out his dorm room until three months after the May 4 shootings.

He returned to a quiet Kent State campus.

“It was sad,” he said. “I was anxious about what was going to happen, but I knew I had to get my room cleaned out.”

Fears of protests and violence lingered, so Kent State University assigned move out dates and times to limit student interaction, Schoolmaster said.

Fall 1970

Lewis said the fall of 1970 was very emotional at Kent State.

Grieving and hugging people could be seen across campus. Students worried about course credits from the previous semester. There were small demonstrations.

Schoolmaster said students were determined to get back to their classes and move forward.

He spent the next nine years at Kent State, completing his Bachelor of Science in education, and his master’s and Ph.D. in geography.

He said his career as a professor was inspired by the ability to do research, flexibility to teach various courses and his last name.

"My last name is Schoolmaster, what else was I going to do?”

Dr. Andrew Schoolmaster. Photo by TCU Magazine.

Dr. Andrew Schoolmaster. Photo by TCU Magazine.

Schoolmaster at the Trinity River teaching students. Photo by TCU Magazine.

Schoolmaster at the Trinity River teaching students. Photo by TCU Magazine.

Schoolmaster in front of the horned frog statue in 2007. Photo by TCU Magazine.

Schoolmaster in front of the horned frog statue in 2007. Photo by TCU Magazine.

The School Master of TCU

In 2007, Schoolmaster became the dean of AddRan.

In his first few years, he helped design Scharbauer Hall, currently home to AddRan and the John V. Roach Honors College.

Schoolmaster carries the lessons of perseverance from his past into the present circumstances.

“I never dreamed it would happen, but we got through it 50 years ago, and we’ll get through it 50 years later.”