Surrounded by bodyguards and the last person to get off the bus, Jerry LeVias thought he was a “big superstar” for Southern Methodist University.To others, he was a dead man walking.

LeVias was the first black scholarship athlete in the old Southwest Conference, a conference of which TCU was a member for 72 years beginning in 1923.

An anonymous caller had vowed, using a racial slur, to kill LeVias if he set foot on TCU’s campus.

During every down, Fort Worth police and the FBI watched for an assassin from locations throughout the stadium. Even the Boy Scouts working as ushers were looking out for the sniper.

LeVias took cover as the rest of the team warmed up between halves, and the team used more motion than any other game that season to make LeVias a harder target to hit on the field.

“I ran faster to the bench than I did on the football field,” LeVias said. “But at the same time, I had to play ball. We couldn’t just call the game off.

“If it was going to happen, it was going to happen.”

It never did.

ROCKY ROAD TO INTEGRATION

LeVias still wonders if anybody watched the Mustangs rout the Frogs 21-0 that day with his No. 23 in the crosshairs.

The rest of the team found out about the threat the next day in the newspaper or on the radio that night. The Mustangs’ coach, Hayden Fry, rarely told the rest of the team about what LeVias was facing that season.

“If he was bearing the burden of this, he was doing it mostly on his own,” said Albon Head, LeVias’ teammate who is now an attorney in Fort Worth.

And it wasn’t the first time LeVias had been threatened.

“It wasn’t totally different from that whole season,” Head said.

He was spat upon. Trainers wouldn’t tape his ankles for fear of touching his black skin. Teammates emptied the showers when he stepped in and alumni threatened to pull their support if he ever played.

“Those were the times,” LeVias said. “Integration was a hard idea for a lot of southerners to swallow.”

Other conferences had already integrated. Fry, who grew up “on the wrong side of the tracks” in Eastland and Odessa, took the coaching job at SMU under the condition that he would be able to begin integrating the conference – despite a time-honored “gentleman’s agreement” among coaches to never recruit black athletes.

“He was the only black face in a whole sea of white faces in the Southwest Conference, and we played seven conference games,” Head said.

Amon Carter Stadium had already seen its fair share of black players, but none came from a conference rival. Lenny Moore and Rosey Grier were the first to appear on the field when they played for Penn State in 1955.

NO SHOW IN 1967

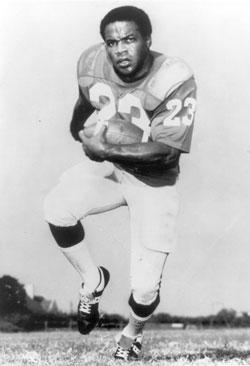

Despite the uphill integration battle, LeVias, at 5 feet 9 inches and 170 pounds, led the Mustangs to a conference title during his first year of varsity play in 1966.

After winning the title, the Mustangs were 2-7 going into a December game against TCU a year later.

This time, LeVias’ No. 23 was nowhere to be seen.

He was checked in to a local hospital under an assumed name, awaiting surgery on part of his skull.

One week earlier, a Baylor defender had tried to poke LeVias’ eye out and damaged the bone near his eye socket.

Once again, nobody knew about the incident, even teammates.

“It was like a covert operation,” LeVias said.

One week and four days later, TCU would join SMU in integrating SWC football, signing Linzy Cole, a Henderson County Junior College transfer sought by more than 40 other colleges. But Cole wasn’t TCU’s first black athlete.

TCU INTEGRATES

James Cash was already driving Jim Crow out of college basketball when Cole arrived on campus in the spring of 1968.

Cash began at TCU as the conference’s first black basketball player the same year the University of Texas at El Paso won the NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship with a team of all-black starters. The new TCU player joined under head coach Buster Brown, at the urging of Chancellor M.E. Sadler.

Both Cash and Cole were standouts during their TCU days.

Cash led the conference in rebounding his senior year and had career averages of 13 points and 11 rebounds per game.

He now sits on the board of directors at Microsoft, Wal-Mart and General Electric, and was Harvard University’s first black tenured professor. He also served on TCU’s Board of Trustees.

Cole, a Dallas Madison High School graduate, went on to play pro football for the Chicago Bears, the Houston Oilers and the Buffalo Bills before becoming a Philadelphia Bell in the World Football League in 1974.

‘I JUST WANTED TO QUIT’

Cole led the Frogs in receiving during his junior year in 1968 – the same year he hauled in a 37-yard pass in Amon Carter’s end zone to put the first touchdown on the board for the Horned Frogs against SMU in mid-October.

Cole’s touchdown set the 1-2 Frogs off to a strong start against the 2-1 Mustangs.

That left LeVias’ Mustangs tied with the Frogs 14-14 in front of 31,542 fans in the fourth quarter when LeVias was taken out by an opposing linebacker’s tackle.

As the linebacker rolled over LeVias, he spat in his face, saying, “Go home, nigger.”

LeVias stormed off the field, discarding his helmet in the concrete gutter against the stadium wall.

“That’s the only time I ever lost it,” LeVias said.

He had already dislocated a finger in the pre-game and was nursing a bruised shoulder and a case of the flu.

As Fry approached the bench LeVias told him: “I quit. I’m not going to take this bullshit anymore.”

Fry wouldn’t accept it, though.

“He just kept saying things like: ‘Don’t let your teammates down. Don’t let this guy get you,’ stuff like that,” LeVias said.

Meanwhile, SMU’s defense was holding off the Frogs at the 38-yard line. It was fourth down and Fry was short a returner.

LeVias shot past Fry saying, “Coach, I’m going to run this one back all the way.”

He fielded the punt at the 11-yard line and ran straight up the middle.

He swerved toward TCU’s sideline, bounced off defender Danny Lamb near the 50 and hit open country. He juked and shuffled the pigskin 89 yards into the south end zone.

LeVias’ run made it 20-14 in favor of the Ponies and a Bicky Lesser kick sealed the deal.

Despite scoring the game-winning touchdown, though, LeVias said that record-breaking run was the least satisfying of his career.

“I didn’t enjoy it because I did it out of anger. I played football for the love of the game and I think that’s the only time I did something out of anger,” he said. “It’s always back there, that one instance when I lost it.”

LeVias, now in his 60s, still hasn’t identified the TCU linebacker that almost ended his career that day but did say the Horned Frog called to apologize after LeVias, along with Fry, was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2003.

“I had friends on that team,” he said of the ’68 TCU team. “I’d played two years varsity and took all that and then all of a sudden that happened. Sometimes you just crack.