While some college students enjoy sitting at the back of their classrooms, junior Chris Dorr sits at the very front. Dorr receives preferential seating in order to accommodate his learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. “During quizzes and other assignments, if I see people it kind of makes me anxious, like ‘Oh, they’re finished, why am I not finished?’” he said. Dorr is one of 404 TCU students currently receiving an accommodation for a learning disability. According to the 1990 Americans With Disabilites Act, a learning disability is a “neurologic disorder that causes difficulties in learning that cannot be attributed to poor intelligence, poor motivation or inadequate teaching.” Common learning disabilities include dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, auditory processing deficit, visual processing deficit and ADD/ADHD. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, of college undergraduates who self-reported having a disability, 11 percent reported having a learning disability. Also, more than 200,000 students who enter college have some kind of learning disability. TCU Student Disabilities Services provides various accommodations for students with learning disabilities — which range from extended time on tests to recorded class lectures — based upon approved documentation verifying “the existence of a disability.” Marsha Ramsey, director of Center for Academic Services, said specialists in the Student Disabilities Services department look for functional limitations when evaluating students’ documentation. “This is about access,” Ramsey said. “If there are barriers, then we’re trying to determine how to remove those barriers so students can demonstrate what it is they know or what they learn.” Looking back Student Disabilities Services was not present at TCU until 1993, with the passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Section 504 of the legislation prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities. [documentcloud url=”http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3227435-section504.html”]

TCU complies with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibits discrimination in education against individuals with disabilities.

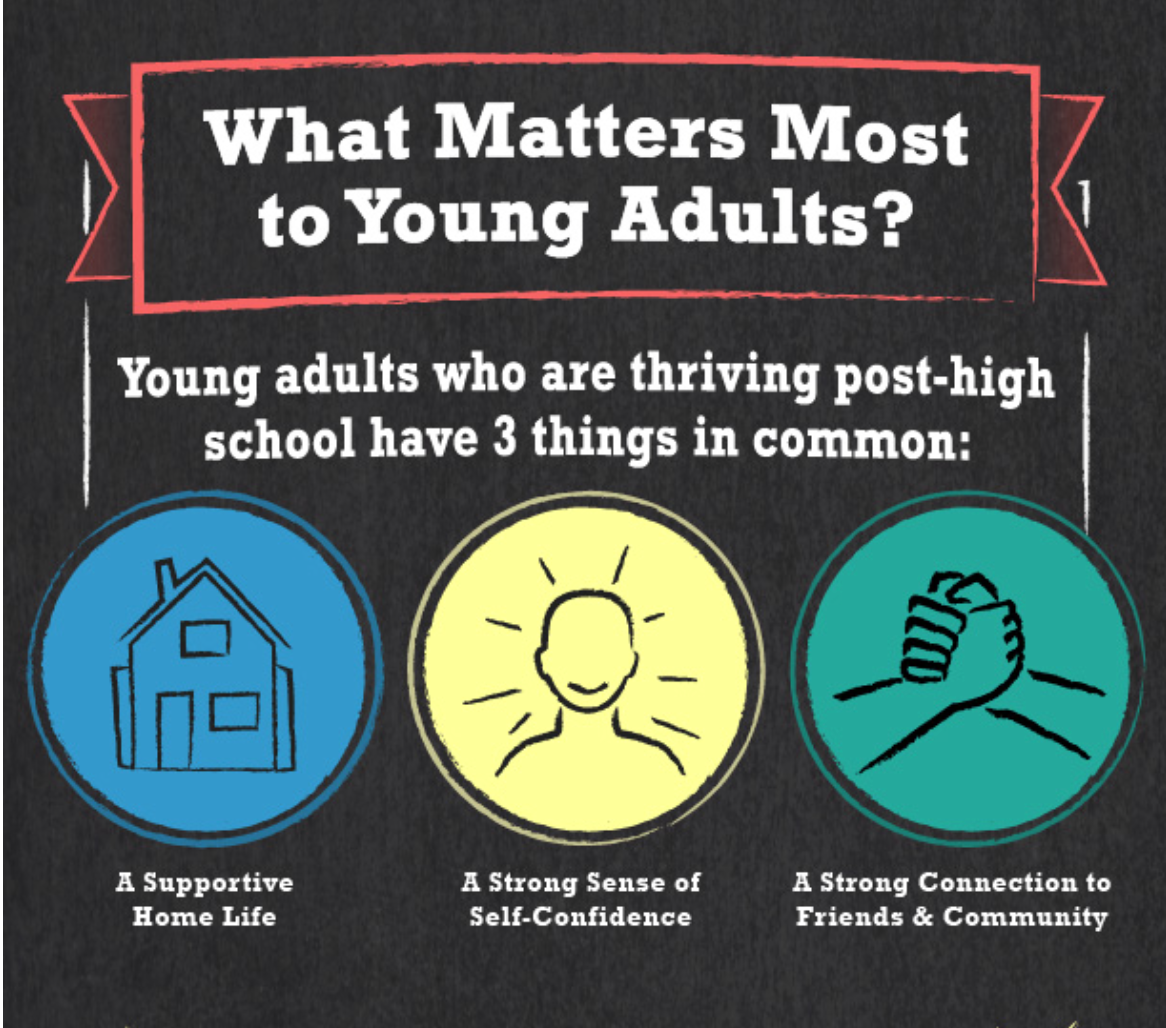

Attaining success at TCU — and academic life in general — may have been tougher for students with learning disabilities prior to the department’s existence. “A lot of the time, learning disabilities were missed. Students just thought they weren’t smart and didn’t realize they had a learning disability,” Ramsey said. “It might also have been that students with a learning disability at that time didn’t wind up going to college because their kindergarten through 12th grade material was so difficult, and if they didn’t know what was wrong, they might just think ‘I’m not college material,’ and decide to go another route,” she added. It also may have taken students with learning disabilities longer to graduate, longer to study and/or the need of extra tutors and support all over campus for whatever class they were struggling in, said LaShondra Jimerson, a disabilities specialist in TCU’s Student Disabilities Services department. Former Director of TCU’s Bachelor of Social Work Program, Dr. Linda Moore, who retired in May, said that prior to the implementation of services and accommodations for students with learning disabilities across universities in the U.S., students with learning disabilities would either not succeed in college or not go to college at all. “Before the Education for Handicapped Children Act in the 1970s, many times kids with any kind of disability wouldn’t go to school at all,” Moore said. “When I was growing up, we didn’t have kids in wheelchairs in schools; we didn’t have kids with developmental delay or lots of disabilities in schools.” Moore also said she believes more students with learning disabilities are in college now because they’re more capable of handling it. “I’ve worked with students that have had learning disabilities 30 years ago who hadn’t been diagnosed and actually had some students that had never been tested that were reading on a third and fourth grade level —not because they couldn’t read, but because they had a disability, and because they had never been tested, they were basically almost failing out,” Moore said. “It’s very different today — students come in with their accommodations in hand.” The first testing for learning disabilities was in the late 1890s, then testing was done after the first World War I soldiers returned from war in the early 1900s finding they could no longer function using the same academic skills they used prior to the war, Student Disabilities Services Coordinator Laurel Overby said. An increase in students with learning disabilities attending school and pursuing higher-level education came out of the Civil Rights movement during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Various groups were fighting for rights — the women’s rights movement, the African-American civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, the American Indian movement — and one of the major groups taking a stand for rights and equality at the time were people with disabilities, particularly parents of children with disabilities. “When parents want something for their kids, they tend to have a lot of power,” Moore said. “So once it got started, you saw people jumping on the bandwagon and the country got lots of legislation — we got the Education for Handicapped Children Act, we got the Architectural Barriers Act, and by 1990, we got the ADA, which is the most comprehensive piece of legislation ever for people with disabilities.” Overby said not much attention was given to disabilities until the 1980s and 1990s, with dyslexia being at the top of the list. “Disability falls under civil rights,” Overby said. “It was finally given a voice.” Student success Some TCU students with learning disabilities say that the assistance from the Student Disabilities Department has helped them greatly. Dorr, a strategic communication major, stressed the importance of his accommodations. “If I didn’t have my extended [test] time, I’d probably fail out of TCU,” he said. “And if I wasn’t able to type my notes, I don’t know how I’d be able to take notes on paper without getting distracted.” He also said he feels like he wouldn’t be as successful at TCU without the existence of the Student Disabilities Services department. “I think for only one or two of my classes I haven’t needed to use extended time on exams, and that’s just one to two classes. This is my first semester of my junior year, so I’ve used a lot of my extended time,” Dorr said. Regan Arnold, a junior entrepreneurial management major, was diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD in fourth grade. She says a large reason she chose to attend TCU is because of the university’s accommodations for students with learning disabilities. “I have worked really hard to overcome my learning disability, so I think that I can be successful on my own, but the fact that they have the resources here really played a part in why I came here,” Arnold said. However, only 17 percent of college students with learning disabilities take advantage of “learning resources at their school.” Trey Fearn is a first-year Film, Television and Digital Media major who says he has a fine motor skills deficiency as a result from concussions during high school. He said he has difficulty processing information and takes longer time to read. “If you give me a Scantron, I can have the answer in my head, but the actual act of bubbling it would take me a while,” Fearn said. He said he has not yet utilized the Student Disabilities Services to acquire assistance for his learning disability, nor has he told any of his professors of it. “So far, I’ve been doing just fine without it, but I will 100 percent start using the accommodations throughout college,” Fearn said. According to a study done by the National Center for Learning Disabilities, the three factors most attributed to success post-high school for students with learning disabilities are a supportive home life, a strong sense of self-confidence and a strong connection to friends and family.