Homelessness in Tarrant County has decreased, but the decline might not last long

Tarrant County homeless agencies anticipate homelessness to increase following the end of the federal eviction moratorium

The number of homeless people in Tarrant County is down sharply according to the most recent census, but homeless agencies and advocates worry the numbers reflect an undercount that could swell when the federal moratorium on evictions ends.

The Point in Time Count, done by the Tarrant County Homeless Coalition between Jan. 28 and Feb. 11, found homelessness decreased by 42% and the number of new homeless people decreased by 35%. 1,234 total homeless individuals were counted, according to TCHC.

By comparison, last year’s survey found 2,103 people experiencing homelessness. The survey occurred before COVID-19 gripped the nation. Shelters functioned at capacity, and 500 volunteers fanned out in teams of three to five across Tarrant and Parker counties trying to get the most accurate count possible of those who have no recourse except living on the street.

Photo: Doc is homeless and sick. Mobile paramedics from John Peter Smith Hospital check in on Doc to make sure his medical conditions do not get worse. (Josh Jordan, 2017)

Photo: Doc is homeless and sick. Mobile paramedics from John Peter Smith Hospital check in on Doc to make sure his medical conditions do not get worse. (Josh Jordan, 2017)

This year, COVID-19 restrictions limited the number of people in shelters, and community volunteers weren’t allowed to help with the census.

“The Point in Time Count, because of COVID, wasn’t quite the big event that it has been in the past,” said Executive Director of DRC Solutions Bruce Frankel.

Coupled with the possible undercount, the impending end to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s eviction moratorium could result in an increase in homelessness by late summer.

The CDC's freeze on evictions

Worried that evictions could push families into shelters where they could be exposed to COVID-19, the CDC ordered a halt to residential evictions in September.

The eviction moratorium has since been extended through June.

However, the job losses brought on by the pandemic worry homeless advocates. They fear that a staggering number of people could lose their homes without the moratorium.

Photo: Housing activists erect a sign in front of Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker's house in Swampscott, Mass. The Justice Department said Saturday, Feb. 27, 2021, that they will appeal a judge’s ruling that found the federal government’s eviction moratorium was unconstitutional. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer, File)

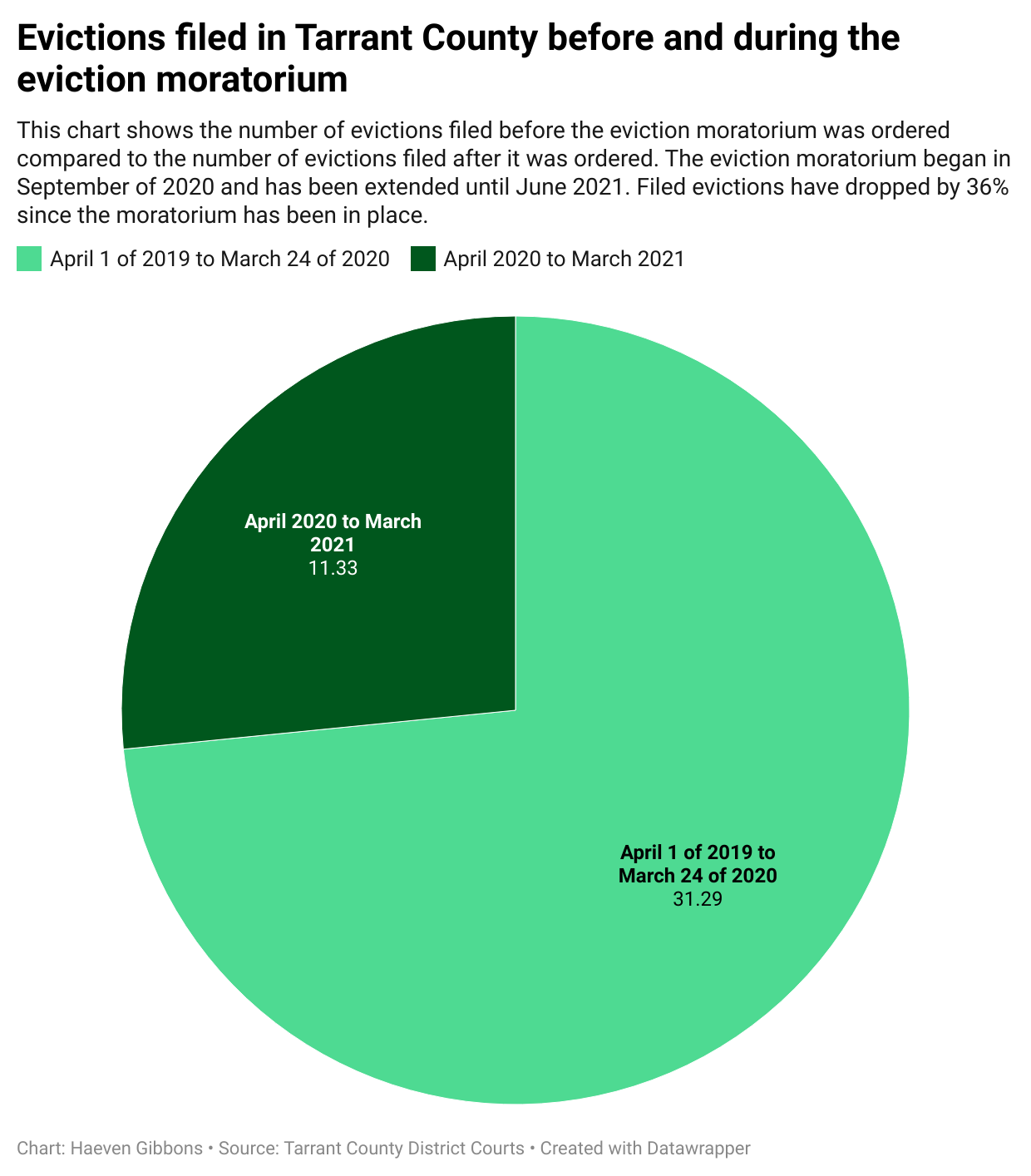

From April 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020, 31,292 evictions were filed in Tarrant County. During the same timeframe the next year , the county saw 11,326 total evictions, just 36% of the pre-COVID-19 numbers.

The moratorium prevented evictions based on delinquent rent payments, but landlords could still remove tenants for lease violations or property damage.

“The general concern is that evictions held at bay until now by federal moratoriums will be filed in large numbers once the moratorium ends,” said the Mobility Coordinator at Tarrant County Kristen Camareno.

Photo: Tenants' rights advocates demonstrate outside the JFK federal building in Boston. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer)

Historically, about 2% of those evicted in Tarrant County become homeless. That number recently doubled to 4%, according to TCHC. If that percentage continues to inflate, the homeless population will increase, said the executive director of TCHC, Lauren King.

The eviction process can take weeks. The time a tenant receives a notice to vacate to the time when the tenant is actually evicted can last up to 30 days.

The increase in homelessness is not going to be an instant flood; it will be more of a trickle, King said.

Justice of the Peace Courts have seen a decrease in evictions since before the pandemic. For a decrease to occur, tenants and landlords had to work together.

“During the pandemic, our court experienced a decrease in evictions, and I believe it was the result of people working together,” said Judge Sergio L. De Leon, the Justice of the Peace for Precinct 5. “You had a lot of landlords who were working with the tenants and a lot of tenants trying to do their part to make sure that they were at least providing some type of income.”

Effects of the moratorium

The average rent for an apartment in Fort Worth is $1,183 a month. However, apartments ranging from $700-1000 a month make up 34% of Fort Worth’s apartment rental units. Landlords of units where the rent averages $940 a month are often individual investors who are more vulnerable to economic blows, according to the Urban Institute.

The majority of landlords in the Fort Worth area are small “mom-and-pops,” or individual investors, who cannot afford to continue to go without income, said TCHC’s Continuum of Care Operations Manager Kimberly Doty.

“You're asking landlords to essentially forgo any income for a year and not be able to do anything about it,” Doty said.

While landlords face losing income, the moratorium has led to adverse effects on housing for the homeless.

Photo- (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File)

Namely, homeless agencies have struggled to find available housing for homeless individuals.

“It’s harder for us to get people housed right now because typically there’s movement in the market and there are vacancies, and right now there aren't,” King said.

These consequences are partly due to the fact that an eviction moratorium has never been done before.

“I've been on the bench for eight years. I've never seen anything like it,” De Leon said. “Prior to my service on the bench, I was constable for 12 years, and I have never seen any type of moratorium related to evictions.”

Photo: Samaritan House is a permanent supportive housing-based agency. They have partner case management and medical services to help clients ease the transition back into a sustainable and healthy lifestyle (Haeven Gibbons/TCU 360)

Plans in place

There are plans in place for when the eviction moratorium ends to prevent people from falling into homelessness.

The Tarrant County Emergency Rental Assistance Program launched last month to assist eligible households who are unable to pay rent or utilities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“By working with our justice of the peace courts to coordinate the Texas Eviction Diversion Program and providing rental assistance through various federal and state funding programs, like the upcoming ERAP, we hope to drastically curb the number of cases filed in Tarrant County when the current CDC moratorium is lifted,” Camareno said.

Other programs help renters with rental relief. The Texas Eviction Diversion Program helps eligible tenants stay in their homes and provide landlords with an alternative to eviction.

Renters can also apply for emergency rental assistance through the city of Fort Worth. Fort Worth’s CARES funds are exhausted, but the City of Fort Worth Neighborhood Services will continue serving residents of Fort Worth and Tarrant County with several assistance programs.

“Apartment managers that are essentially the usual clientele of justice of the peace courts, were doing their due diligence to make sure that they were referring their tenants to these programs,” said De Leon.

While prevention funds can be approved by the city, it is up to the landlord to decide to accept them, Doty said.

“We wouldn't be a year into the pandemic with a moratorium in place, if prevention funds and the eviction moratorium would have rolled out hand, hand in hand,” Doty said.

Homeless agencies brace for impact

Despite the programs in place, TCHC and its partners are “bracing for impact,” King said.

TCHC is looking at ways to safely increase shelter capacity if homelessness does increase once the moratorium ends. Right now, shelter capacities are still at 50% due to COVID-19 restrictions.

To prevent people from falling into homelessness, TCHC is focusing on diversion training.

Diversion requires identifying additional supports people may have that they are not currently using.

“Our biggest thing that we're doing to prepare for this summer is actually training staff,” King said.

TCHC trains their staff to know what questions to ask and what to listen for when trying to identify additional supports that an individual may be able to access.

The coalition is also preparing by assessing how they can use funds to quickly move people out of homelessness, making sure their municipalities are aware that eviction prevention money is available. They also work with landlords through the landlord engagement program to make sure the tenants get the help they need.

DRC Solutions, a homeless agency and service partner of TCHC that focuses on housing, is prepared to respond with emergency shelter if needed.

The DRC coordinated and opened an emergency shelter last summer when the economic recession caused many individuals to fall into homelessness. The group had 48 hours to set up the emergency shelter for 400 people.

“We have become experts in being able to operate emergency overflow shelters to meet that capacity,” Frankel said.

Even with the decrease in homelessness and overall number of evictions, the numbers are still large, which is “nothing new,” according to De Leon.

“There's a larger discussion that needs to be had about how we address our housing problem,” De Leon said.

Many people cannot afford the high rental rates, especially in the inner city.

Long-term conversations must be held by the city council, commissioner's court and state legislators to ensure the systems in place do not create a cycle of more and more evictions, De Leon said.