Nebraska meatpacking workers vulnerable to COVID-19

Federal and state regulations fell short in protecting essential workers

More than 100 years since Upton Sinclair wrote “The Jungle,” workers in the nation’s meatpacking plants still face unique vulnerabilities due to the nature of their jobs.

Workers in the plants have been especially hard hit by COVID-19. As of July 1, Nebraska reported 19,310 cases and 237 deaths. While the numbers are declining, an examination of the state’s spring outbreak reveals a different story.

In May, four Nebraska counties ranked in the top 20 cases per capita in counties across the country, according to data compiled from state and local health departments and the U.S. Census Bureau by USA Today. These counties experienced outbreaks at the meatpacking plants. Some plants closed. Some remained open. There was no unified or codified federal or state effort to protect workers, so the virus spread rapidly.

Nebraska was one of seven states that never issued a stay-at-home order. Gov. Pete Ricketts also encouraged these plants to remain open and declared May “Beef Month” even after the outbreaks and deaths of workers.

The per capita growth of the outbreak in Grand Island, Nebraska, in Hall County matched the spread in New York City, according to reporting from the Omaha World-Herald. Grand Island’s largest employer is the JBS USA’s beef processing plant, which employs about 3,600 people in a city of 51,478 people.

Dakota County in Nebraska has also been hit hard by the virus and ranked second in per capita cases on May 23. As of May 29, 786 of the town’s Tyson Foods plant’s 4,300 employees tested positive. The plant had closed briefly for deep cleaning from May 1-4.

Saline County, home to a Smithfield meat processing plant in Crete, was another hotspot in the state. There have been 537 cases in the county of 14,350. Local workers staged a brief, impromptu walkout.

The concentration of cases prompted the University of Nebraska Medical Center to survey meatpacking workers across the state May 7-25. The results show while plants checked workers for symptoms, the workplaces weren’t always fully adapted to deal with the novel coronavirus.

For example, while more than 80% of those surveyed said they were checked daily for fever and were required to wear masks, more than half also said they could earn bonuses for “completing scheduled shifts.” Only 56% reported an increase in cleaning, and only 40% said the distance between workers was increased.

Almost a third of workers in the survey reported they had not heard any information from their employer about COVID-19.

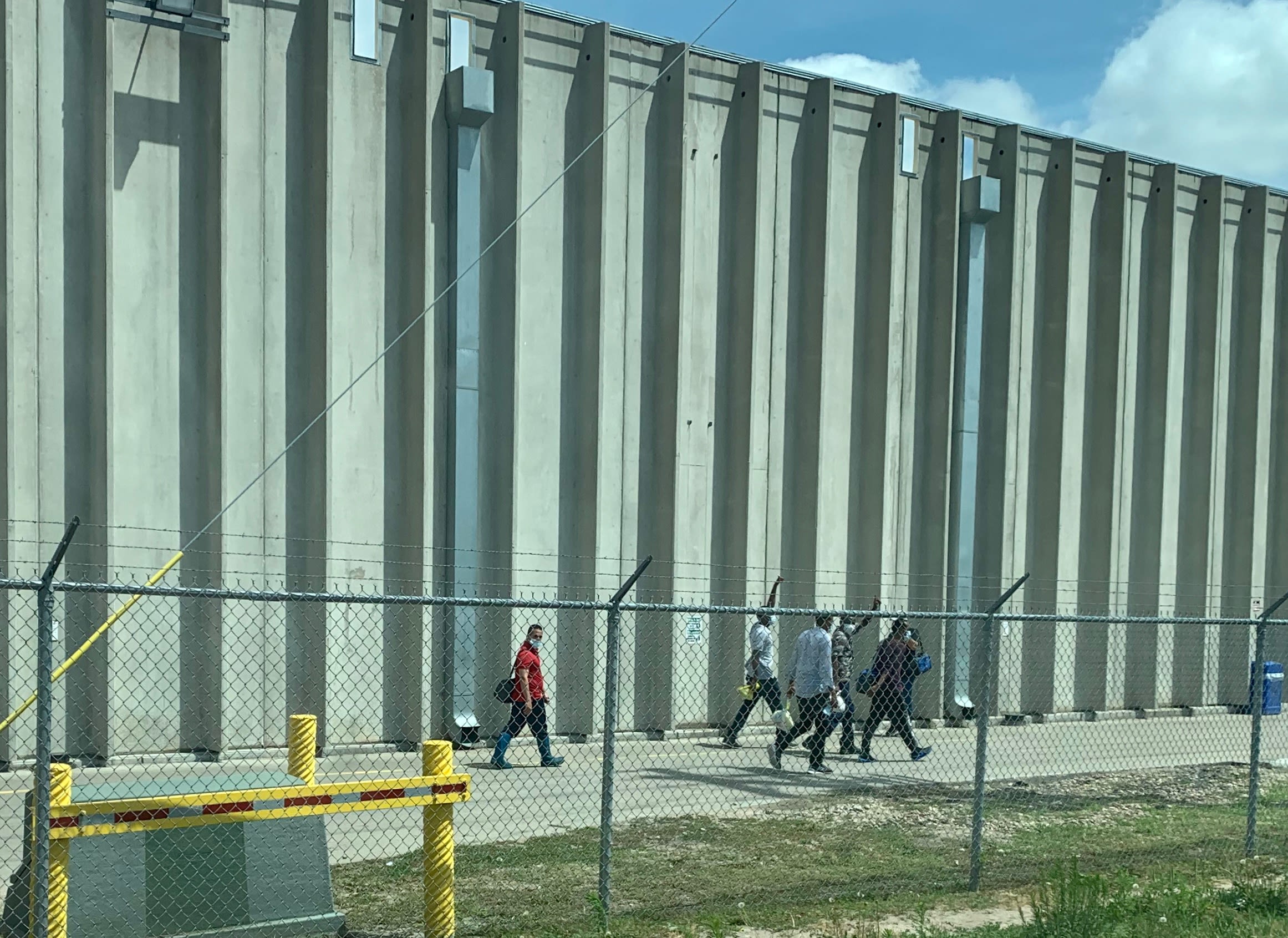

(Chris Machian/Omaha World-Herald via AP)

(Chris Machian/Omaha World-Herald via AP)

(Chris Machian/Omaha World-Herald via AP)

(Chris Machian/Omaha World-Herald via AP)

The survey found that workers felt pressured to come to work even if sick, said Dr. Athena Ramos, an assistant professor at the UNMC College of Public Health, who led the survey. Workers reported “pressure coming from the supervisors requesting people come into work if they were sick, or not being able to spend . . . their full two weeks out,” she said. Some reported they were required to return to work early, or “pressured to figure out a way to get through the screening process at the entrance of the plant.”

Ever since Upton Sinclair exposed the appalling conditions in the U.S.’s early meatpacking industry in "The Jungle," consumer and worker safety have been an expectation in meatpacking plants' conditions. But they often compete with consumer price expectations.

“For better or for worse, we live in a society where we like our food cheap, inexpensive, and safe,” said Bob Ogren, the vice president and general manager of Birko Corp. Equipment Division, a food safety equipment supplier. Americans expect inexpensive meat in grocery store shelves, pandemic or not.

An essential industry

Working conditions in this industry are demanding and largely physical, with workers side-by-side, working at high speeds to produce as much beef as possible. Common areas such as cafeterias and locker rooms are also cramped. Close conditions like these accelerate of the spread of the respiratory virus.

Read more: Tyson Fresh Meats plant leads to a spike in COVID-19 cases in one county

Initially, some meat and poultry packing plants temporarily closed to manage the outbreaks. But President Donald Trump issued an executive order April 28 that deemed meatpacking plants “critical infrastructure” under the Defense Production Act. “Given the high volume of meat and poultry processed by many facilities, any unnecessary closures can quickly have a large effect on the food supply chain,” said Trump.

The order didn’t outline mandatory regulations to protect the essential workers and public safety, but it did offer suggestions and guidelines recommended by the CDC and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

In September 2019, Trump approved more lenient guidelines and regulations of the industry that critics said put more workers at risk. The president approved a decrease in USDA regulations of hog plants.

The elimination of maximum speeds in the production line, means speeds can be increased.

According to OSHA meat plant workers are in a job that already poses three-times greater risk of injury than the average job. Even before the pandemic, the president's actions prioritized profits and production more than the risks faced by meatpacking workers, critics argued.

(AP Photo/Nati Harnik)

(AP Photo/Nati Harnik)

Economic impact

Beef is an essential driver of Nebraska’s economy. Meatpacking plants and their workers are essential to beef production. According to the Nebraska Beef Council, $6.5 billion is produced in the industry each year. JBS is a key company, paying local producers nearly $2.5 billion a year.

Ricketts focused on maintaining production and supply lines, rather than providing transparency to workers and their communities. During a daily news conference on May 6, Ricketts said health departments would no longer be announcing the number of COVID-19 cases from the specific plants, as it was a violation of workers’ “health privacy.”

Additionally, at a press conference June 15, a Dakota County reporter asked Ricketts if counties that required masks would receive Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) funding. Ricketts said any county that required masks in local courthouses would be denied CARES funding, leaving counties to decide between abiding by CDC recommendations or receiving recovery funding.

At first glance, the state’s declining COVID-19 numbers seem like a relative success.

For most Nebraskans, this summer seems largely normal. Contact sports are beginning practices, public swimming pools and bars are open, and indoor and outdoor events can return with physical distancing.

Nebraska is in phase three of reopening, except for Hall, Hamilton, Merrick and Dakota counties, which were all affected by the meatpacking plant hot spots.

These plants are the largest employers in many rural communities. In the UNMC survey, 67% of workers surveyed were from Mexico and Central America.

Although physically demanding, the jobs attract workers by paying well and offering benefits. The median pay is $13 per hour, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Taking Action

Healthcare is the second largest employer behind JBS in Grand Island. Meatpacking workers who had contracted the virus needed treatment and local healthcare workers were there to help.

“It literally lands on our doorstep. I mean, these are our patients,” said Dr. Libby Crockett, a local Grand Island physician. Crockett used to work at the UNMC College of Public Health and reached out to the highly trained infectious disease team to visit the plants and offer guidance.

The group visited JBS and other plants starting in April to address the gap in guidance. They created a Meat Processing Facility COVID-19 playbook with guidance for the plants across the state, including implementing strategies like paid sick leave, increased ventilation and more physical distancing.

Cases have declined since these strategies were implemented in the plants and local public officials enforced stricter messaging in the Grand Island area.

According to the Central District Health Department, the week of May 1 yielded the highest number of positive cases, 369, whereas last week’s tests yielded only 17 positive tests. Even though the cases are mostly under control and life is returning to normalcy in Grand Island, community members remain vigilant in advocating for worker protections.

JBS announced June 25 its “Nebraska Strong” initiative. The company will be donating $4 million to invest in Nebraska communities and add more COVID-19 preventative measures.

“The rural towns and communities where we live and work are the key to our success and Grand Island, Nebraska, is home to one of the centerpieces of American agriculture,” said Tim Schellpeper, the president of JBS USA Fed Beef in a June 25 press release announcing the initiative.

Community members aren’t convinced yet. The Solidarity with Packing Plant Workers group has organized a weekly car vigil where community members decorate their cars and drive around Grand Island, Lexington and Omaha to show support for the workers. The group advocates for increased transparency from the meatpacking plants on COVID-19 cases, paid sick leave for all and personal protective equipment (PPE) for all workers.

“We need our essential workers to be healthy, so they can continue to support their families and feed this nation and around the world,” said Tim Lentz, a resident at the protest on June 27.